On April 14 2019, the 117th edition of the world-famous one-day bicycle race “Paris-Roubaix” will be held. But Paris-Roubaix is not just any bicycle race: it is the cultural reassurance of a whole region and it is also a memorial of European history.

Paris – Roubaix is a professional bicycle race different from all the others. It is known as the “Queen of the Classics” or “The Hell of the North” and is said to be one of the toughest one-day races in professional cycling.

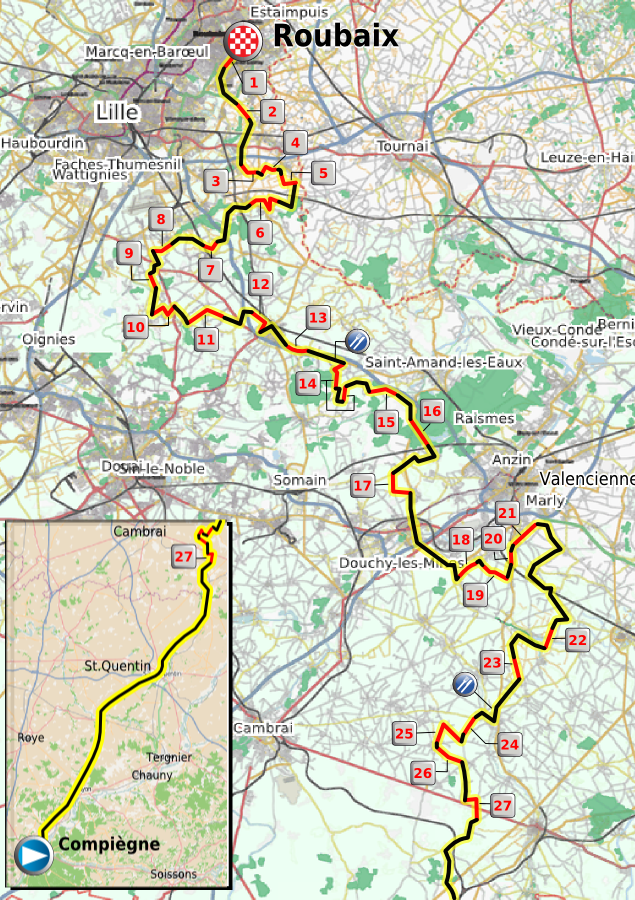

The name of the race itself is slightly misleading. In fact, the race begins in Compiègne, some 70 kilometres north of Paris, clearly indicating the general direction of the course is northbound. The geographical setting of the race is the region of Hauts-de-France and more precisely the regions Oise, Somme and Aisne, with the most important part including the finish taking place in the Nord region.

Archaic roads and natural forces

One component which makes the race one of the hardest in professional cyclists’ calendar is the geographical and climatic aspect. In Spring, the weather is very unsettled and the race is often accompanied by strong winds, rain and often even snow. A second, and the most unique, component is the fact that over one-fifth of the 250 kilometres of the race lead the riders on cobbled streets. And these aren’t cobbles from paved city centres but unevenly paved cobbles with considerable gaps which one already feels walking on these streets. Professional cyclists trying to master the course often express their love-hate relationship with the race.

Although they seem very anachronistic in the 21st century, no one would like to see the cobble roads being replaced by asphalted roads. These are the unique selling point of the race and have made it famous with cycling enthusiasts around the world, giving the region back some of its lost pride. A pride which has partially gone lost during the last century.

The region in a dramatic downturn

Once one of the strongholds of coal mining and therefore the heart of the industrial revolution in Western Europe, the region underwent a slump during the second half of the 20th century. Since the 1960s, coal mining got increasingly difficult because the deposits easiest to exploit had already been extracted and it subsequently got unprofitable, forcing the mines to shut down one after the other. The last mine in the “Bassin du Nord-Pas-de-Calais” was closed down in 1990. The downfall of the mining industry plunged the whole area into an economic downturn and provoked considerable socio-economic disruptions. Unemployment rates in Nord Pas-de-Calais rank among the highest in France. A fate which is shared with other former mining regions in Western Europe like the German Ruhr area or the Belgian region of Wallonia.

Unequivocally, one of the most remarkable parts of the race is the passage of the “Trouée d´Arenberg”, a 2.3-kilometre long cobbled forest aisle above a mine, decommissioned in 1989. The former mine is part of the “Nord-Pas de Calais Mining Basin” UNESCO World Heritage and gets featured prominently every year during the television broadcasting. This passage has become a fixed point in the world of professional cycling and is the symbol of Paris-Roubaix and the physical suffering of the course.

Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle, a two-time Roubaix winner, was once cited with the following words: “You cannot ride Paris-Roubaix without suffering. The people of the north appreciate what you’re doing because it gives them the impression that you’re a bit like them – people who work down the mines.”

Indeed, being along the course, you immediately get the sense that the inhabitants see it as “their” race. Every village along the route seems to burst in excitement and anticipation, every household and each generation seems to be on the streets and enjoys being at the centre of attention of the global cycling community.

The real ‘Hell of the North’

It is often believed that because of the “Trouée d´Arenberg” and other cobbled sections, which makes Paris-Roubaix one of the hardest races in the professional cycling year, the race is also commonly known as the “l’enfer du Nord”, the “Hell of the North”. Even though it might be obvious to relate this nickname to the difficulties, its origins date back to the early years of the race and does not have a sport background at all.

The North of France was one of the major areas of World War I, casualties of both warring parties on the Western Front reached millions. When the ceasefire agreement between France and Germany was signed in Compiègne, villages and cities were almost levelled to the ground. Among the victims of the war were also winners of four pre-war editions of Paris – Roubaix, which was interrupted during the war years and resumed immediately after in 1919. Against the background of the cataclysms World War I brought over Europe, doubts were certainly justified if it was really necessary to hold a sports event as if nothing had happened.

However, the organisers, the French sports newspaper “L´Auto”, decided to do so and got Victor Breyer and Eugène Christophe from Paris to the North to see if the streets were passable for the first edition of the race after the war. Bluntly spoken, they had to check if cities along the route like Amiens, Arras, Lille or Roubaix still existed.

Victor Breyer’s report is an impressive historic document: “Shell-holes one after the other, with no gaps, outlines of trenches, barbed wire cut into one thousand pieces; unexploded shells on the roadside, here and there, graves. Crosses bearing a jaunty tricolour are the only light relief.”

“The shattered trees looked vaguely like skeletons, the paths had collapsed and been potholed or torn away by shells. The vegetation, rare, had been replaced by military vehicles in a pitiful state. The houses of villages were no more than bare walls. At their foot, heaps of rubble. Eugène Christophe exclaimed: ‘Here, this really is the hell of the North.‘”

As an observer of the race, one should always have in mind that the real battles in this region took place in the trenches of World War I and the battlefields of World War II. And what is just the physical pain during a bicycle race thana pale comparison to what young men on the frontline and the population went through centuries ago.

Freely adapted from Sartre: l´enfer c´est les autres. Hopefully, “les autres”, the others, are the horrors of two brutal wars in the 20th century, wars which are hopefully forever a matter of the past.

Feature image: Rear of the peloton during the 2013 Paris – Roubaix | Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0