For the latest in our Creative Conversations series, E&M called up Portuguese poet, performer, and art-educator Raquel Lima. She talked about performing poetry, writing as a political act, and her wishes for 2021.

E&M: Hi! Thank you so much for talking to us. How would you introduce yourself to our readers – who are you as a creator?

Raquel: I grew up in the Southside of Lisbon, in Miratejo and Almada, with the typical influences of growing up in the periphery of a big city, with hip hop, hardcore, punk, spoken word and street art playing a very important role. That really shaped my identity, regarding what I understand to be the role of disobedient, interventional, and radical art. Then, I started to study Artistic Studies and eventually worked as a cultural producer in Brazil, Paris and Portugal, mainly in contemporary dance, but also theatre, cinema, videoart, and more. Increasingly, I tried to find and create my own spaces to work; I set up a cultural association with some friends, and, later, a poetry and performance festival. Then, I wanted to continue thinking more deeply about arts, activism and society, so I started my PhD two years and a half ago, and I focus on orature and slavery in San Tome. As an academic, I was also part of the organization of an international conference called Afroeuropeans: “Black In/Visibilities Contested” in 2019. Meanwhile, as a poet, I published my poetry in several languages and my first book and audiobook of poetry, Ingenuidade Inocência Ignorância, came out in October 2019. As a spokenword artist, I performed in over a dozen countries in Europe, South America and Africa. During this period, I presented my work in literature, oral narration, poetry slam, spokenword, performance and music events. Finally, as an art-educator, I have been organizing poetry workshops, for example on intersectional poetic writing.

E&M: You’ve written and performed across continents and over many years. When and how did you start?

Raquel: Sometimes, I believe that I started writing seriously first, and only started to perform after, but, looking back, I’ve realized it’s the other way around. I have been writing since I was fourteen, I always liked to write, but the possibility of sharing my poetry in the format of spoken word and poetry slam events was the main motivation to continue writing more seriously. For me, poetry was always some raw material to work with, in a pedagogical, ethical and also political way through performance; it was not so much something that I only do as an intimate writing endeavour, performing and sharing was an engine for writing.

E&M: You grew up in Lisbon, your mother is Angolan, your father Santomean, your maternal grandmother Senegalese, and a Brazilian maternal great-grandmother. How has this shaped you?

Raquel: I am still trying to find out. A big part of my subjectivity is Portuguese, yet I grew up with my mother, so Angolan culture was always present, Angolan food, music, dance and even daily rituals or specific ceremonies. Regarding San Tome and the fact that my father was absent, it gave me a lot of curiosity about that side of my life. I finally did an artistic residence in San Tome for one month in 2013 with my association, and now my PhD is on San Tome. And Senegal… I try to learn Wolof [language spoken in Senegal], I try to learn how to play the sabar and how to dance sabar, so I have this African imagery always present as something very concrete but also something very abstract. Finally, I lived in Brazil, and worked there and this is where I grew up spiritually. I’ve got a very strong connection with the territory and I feel deeply at home in places like Rio de Janeiro and Bahia. In my poetry, these dimensions appear in a format of frustration, idealisation, also maybe revolt. In some poems I wrote about my eternal digging to find roots, to find references, to find my ancestry, so I think my background has definitely shaped me. But it’s also a phenotypical issue, it’s not just about nationality, it’s about being Black, and about knowing that we always have this extra work of addressing erasure in our lives.

E&M: What does it mean to you, to be a Black woman writing, in Europe?

Raquel: I believe that there are several possible meanings given the uniqueness of every Black woman, writing, in Europe. But thinking about what I believe brings us together: On the one hand, we are writing from a position that is still impacted by oppression, segregation, erasure, misrepresentation, cultural appropriation and stereotypes. So, being a Black woman writer can be exhausting sometimes, depending on how we negotiate our dissent within our creative process, the editorial market and the different contexts where we present our work. On the other hand, I believe that writing in the African diaspora implies celebration, love and family, and art can fulfil this path of healing, repair and encounter. So for me, being a Black woman writer in Europe is also about celebrating the fact that we are multiple and our identities are fluid and multifaceted, and therefore our imagination and dreams can be very broad, and our writing extremely in-depth.

E&M: What is the last poem you wrote?

Raquel: My last poem was a big one, I think one of my biggest. I wrote it in March. And it is about the end of the world, because we had just entered into lockdown then. And the title of the poem is ‘daydreams of a mortgaged democracy’ – it’s basically a poem that is trying to question democracy as a political and social organization that is condemned to fail. So, it’s a poem where I tried to express how democracy was never shared with everybody. The poem talks about minorities, it talks about Blackness, it talks about capitalism. It’s not a very hopeful poem, it talks about the third world war that we’re living. It was a good way to express what I was feeling at that time.

E&M: As a writer and a scholar, you are involved in social justice. Is your art inherently activist?

Raquel: That’s not something I can control in a programmatic way. When I write a poem, I do not say ‘now I’m going to write an activist poem’. I’m just expressing what I feel. If you’re concerned with social injustice, you will end up having your poetry contaminated by that. Still, I also write more contemplative poems, they talk about life, they talk about death, love, they talk about rivers. It depends on the moment and how the emotions cross me. There are even poems that I write thinking about love and, in the end, someone says ‘this is a very political poem’. So, my poems are also subject to constant interpretations and attribution of meanings

E&M: Political or not, why do you write?

Raquel: That’s a very difficult question. I write because I need some space and some privacy, for sure, and I want to have the possibility of reorganizing everything I live and feel in a very specific, honest way. But I never just write for myself, I write because I believe that poetry can touch people in a very particular way and that we can create a different kind of dialogue, one that is not based on academic norms or on activist codes. It creates the possibility for love, love as movement, I believe that poems can touch people in that way, even if it’s just for a moment.

E&M: Your book “Ingenuidade, Inocência, Ignorância” is also an audiobook. How did you decide to publish your poetry not only as written, but also as spoken?

Raquel: That was completely inevitable, because coming from performing poetry, I understood that there are a lot of elements that cannot just be printed. There is hesitation, breathing, rhythm, insecurity, gestures, elements that need to be transmitted in a more corporeal way, where your body is present. I did an audiobook with the belief that people will have a different awareness of who I am, because they are not only reading my work, but they’re also able to listen to me, they can give a tone to what I write. For me, this is a more complete version of what poetry means – of course, written poetry is also beautiful. But if I can put my body on my work, I will try to do it the best I can, with all the complexities it involves.

E&M: What is your wish for 2021?

Raque: What do I want? I would like for us to become not only more empathetic, but to compromise with one another more often, I also hope to do that myself. And I hope that, basically, we can just be more human and that we can understand our spiritual side. That’s something that’s been bothering me a lot lately, this separation we learned, that body and mind and emotions and spirit are distinct, I think that’s troubling us a lot as humankind. Yes, for 2021, I hope that people can find their spirits.

We thank Raquel Lima for her time. Answers may have been edited for brevity or clarity.

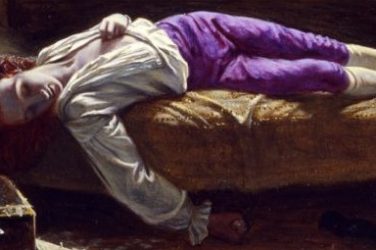

Cover photo: Raquel Lima, taken by Paulo Silva