Can comics bring real-world issues closer to reality? Francesca Jenner investigates for E&M.

Syria is rarely out of the media spotlight today. Headlines and news reports are dominated by stories from the country, whether it’s refugees fleeing the conflict, Western missiles falling on enemy targets, or terror attacks carried out in European cities by young people on behalf of so-called Islamic State.

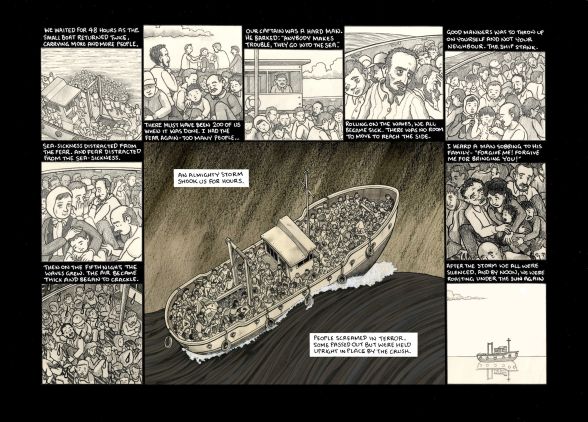

It’s in this context of war and instability, PositiveNegatives produced A Perilous Journey, a trilogy of comics telling the real-life stories of Khalid, Mohammad and Hasko – three Syrians who’ve escaped their home country for Europe. Funded by Norwegian People’s Aid, written by Benjamin Dix, illustrated by Lindsay Pollock and animated by Wael Toubaji, the comics were launched at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, Norway, on 12 November, the day before the Paris attacks. The timing couldn’t be more fitting.

The stories in their illustrated form, with only short text captions, seem able to express and communicate human experience in more depth than is possible to achieve with brief news reports and images, or at least that is the hope of their creators.

According to Dix, “the project aimed to humanise a complex subject involving thousands of people by focusing on individual stories, relating personal experiences through first-person narratives.”

The comic strips, published in the Guardian, tell the individual stories of the men, from violence and torture in Syria, to the sacrifices they’ve made to reach Europe, treacherous boat journeys across the Mediterranean, along with the stark reality of arriving tired and disoriented in an unfamiliar place, with no home to go to.

Graphic novels and conflict

This isn’t the first time a comic book format has been chosen to express the dark and uncomfortable subject matter of large-scale conflict. PositiveNegatives, the producers of A Perilous Journey say on their website, “there is an expanding genre of comic-book literature, autobiography and journalism intended for adult readership.”

The graphic novel Persepolis is a personal account of the author Marjane Satrapi’s childhood in Iran during the 1979 Iranian revolution and the war between Iraq and Iran. The two volumes have sold more than a million copies around the world, and been translated into 25 languages.

Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, published in 1986, is one of the most well known graphic novels and depicts the human suffering of the Holocaust and life under Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 40s.

One particularly moving scene involves the youngster Mohammad reaching Hungary, having travelled by foot and road for days, only to be arrested, incarcerated, and cast out to discover the barbed-wire fence closing off Hungary’s borders. To know that his father used all his savings to help his son reach a better life, is heartbreaking.”The people I met and interviewed were like anyone else, husbands, daughters, brothers and sisters and mothers. They were trying to live a safe life, and given the choice, they would have stayed at home, in their native land – but life doesn’t always play out like we’d hope,” said Dix.

Personally, I felt moved to see how one young man, and surely there are others like him, could set out with determination and optimism for something better, and be crushed by the lack of compassion or empathy he received on approaching the place he thought would offer him shelter, and a future. “I’m a human being with hopes, dreams, basic needs, just like you” is the story this comic seems to be telling the reader.

Humanising refugee stories

Focusing on personal stories somehow makes it easier to connect with the wider issues of war and mass migration that can appear far away. As the often-quoted saying goes, a single death is a tragedy, but a million deaths is just a statistic. Hearing about the numbers of people fleeing Syria can be hard to absorb.

The UNHCR estimates that since the beginning of the Syria crisis until November of this year, close to 700,000 Syrians have applied for asylum in Europe. Neighbouring countries are now hosting over 4 million Syrian refugees: Lebanon has close to 1.1 million refugees, while Turkey is currently home to 2.18 million Syrian refugees – more than any other country.

It’s the world’s worst humanitarian disaster since World War II and yet public opinion throughout Europe is often skewed against immigration. This is increasingly the case in France, in the wake of events in Paris, with Marine Le Pen’s hardline Front National gaining ground in the first round of December’s regional elections.

The unfortunate news that at least two of the Paris attackers entered into Europe posing as refugees did little to help the political situation. But in lumping everyone together and portraying refugees as somehow ‘other’, we distance ourselves from the humans behind the story.

Reading the accounts of Khalid, Mohammad and Hasko, it’s easy to imagine being in their shoes, and that faced with the same tough choices, such as whether to stay in Syria and possibly starve, or be killed; or make the journey to Europe, where there’s hope to get a job and earn some money – most of us would make the same decision as they’ve done.

At the same time, it’s hard to know how things would be if the situation was reversed. If we in France or Belgium say, had to make that same perilous journey in the other direction, to Syria and its neighbouring countries, would things be different? Or is fear and suspicion of refugees a response that could arise in any country or region of the world?

While we should avoid over-simplistic “us” vs. “them” ideologies, I wonder if we should also be wary of oversimplifying the situation with a kind of good v bad morality. It could be argued that one of the downsides to the comic strip format is essentially presenting complex issues with a simplistic narrative. It’s hard to go beyond this with only a few pages.

And yet, it’s also this simplicity that gives the comics their power. The takeaway messages of the comics are clear and unambiguous: what we need more than ever in Europe is empathy and tolerance. Rather than closing our borders out of fear and turning inwards, we should protect and assist people who are desperately seeking a way out and to help their families. The challenge is to spread those messages beyond the already converted.

Featured image: courtesy of PositiveNegatives