E&M’s author Richard Palomar explores the unexpected link between TV anime and contemporary Catalan history, examining the importance this piece of media had on Catalan identity creation.

A European Case

Since the end of the Cold War, a phenomenon of Europeanism continues to consolidate itself, partly as a protest against the “authority of national capitals by people who see themselves as belonging […] more to ‘Europe’ than to a nation-state of clouded origins and dubious boundaries”1. Parallel to that, cities and regions in Europe are developing more professional bureaucracies and have acquired bigger budgets for their individual needs, drifting authority down from national capitals to provinces and cities at varying speeds and to varying degrees.

The growing impact of regions and super-regions and less importance of transnational communities also affects how media is produced, distributed, and consumed. With this shift towards a more regional approach to identity creation, mainstream media –such as television and cinema– also take advantage of this shift.

The Tumultuous Case of Catalonia

From 1939 to 1975 the Spanish State was under a dictatorial regime ruled by Francisco Franco and was commonly known as ‘Francoist Spain’ (España franquista) or ‘Francoist dictatorship’ (Dictadura franquista). During this time, Spain’s minority languages were radically suppressed in their public use, as the government revoked their official statute and recognition. During the 1960s, said policies became more lenient, yet after some decades of no adequate language instruction the level of competence in Basque, Galician and Catalan had drastically declined. After Franco died in 1975 and during Spain’s transition to democracy, an already-existing movement of separatism arose among some Catalans. One of the main aspects of this separatist movement was the cultivation of the Catalan language, which was the regional language that best survived the Francoist language prohibition. As the first democratic government implemented regional public televisions that broadcasted its content in its respective regional languages, TV shows and movies became a core part of the ‘new’ Catalan identity.

“Spanish Catalonia tends to think of itself as a nation, not a region”²

TV3, the primary television channel of the Catalan public broadcaster, played a central role in the creation of said new Catalan identity, broadcasting exclusively content in Catalan and sometimes Aranese, a form of the Occitan language spoken in the Val d’Aran, in north-western Catalonia. From 2001 to 2003, and again since 2010, TV3 has had the leading audience in Catalonia for more than half of the year (more than six out of the 12 months). In fact, 2013 was a record-breaking year as TV3 was the leading audience channel in all 12 months.3

The Arrival From ‘Far East’

‘Anime’ is a term used to describe animation produced in Japan, even though in its original language Japanese the term itself describes all kinds of animated work. The first countries where anime arrived outside of Asia were Italy, Spain, and France, where Heidi and Barbapapa became cult TV shows for children in the 1970s and 1980s. In Spain’s case, the arrival of anime coincided with the end of the dictatorship. As the series were already written, animated and edited, the only work left to do when exported to another country was to translate and dub the series.

A Balearic origin

In the beginning, the Catalan dubbing was financed by entities like Òmnium Cultural and the bank La Caixa, until 1980, when the Balearic philologist Aina Moll Marquès, Secretary of Linguistic Policy of the Government of Catalonia (Secretaria de Política Lingüística de la Generalitat de Catalunya), decided to sponsor dubbing into Catalan for TV and cinema due to its cheap selling price and productive output. From that point on, anime programs began to be a part of Catalan TV and a core part of the Catalan identity creation, as some of those shows were also broadcast in other regions of Spain, but were far less popular and were dubbed in Spanish, a language spoken by 400 million people scattered across the continents.

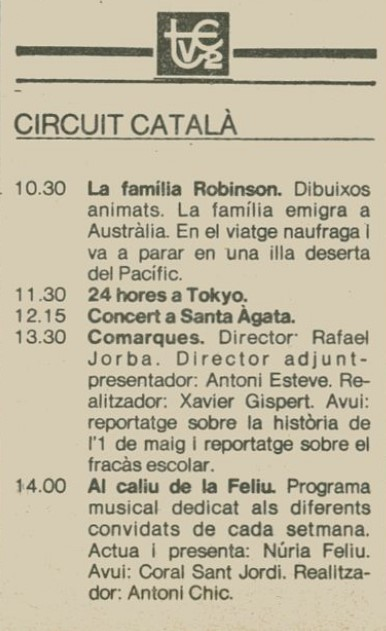

The channel TV2 of Televisión Española (Spanish television) was the first channel to broadcast anime in Catalan in 1984, with the series La família Robinson (The Robinson family). However, it wasn’t until later that anime series became a true central element of Catalan culture, with series such as Dr. Slump (1987), Bola de Drac (Dragon Ball) (1990) and Doraemon (1994). The broadcast of Bola de Drac is considered to be a cultural mass phenomenon, which may partly explain the large reception currently received by manga and anime in Catalonia. Another series that was a fulminant success in Catalonia was the TV series Shin-chan. This anime started airing on the children’s and teenager’s channel K3 in 2001 and became a cult TV show during the 2000s and 2010s. A key moment of its success was the release of the movie Shin-chan a la recerca de les boles perdudes (Crayon Shin-chan: Pursuit of the Balls of Darkness) in 2003, six years after its original release in Japan. This movie had special significance in Catalan cinema, as it was one of the few films that could be seen only in Catalan in Catalan cinemas.

Since then, over 400 anime movies, series and miniseries have been broadcast in Catalonia dubbed in the Central variety of Catalan, mainly spoken in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia. Over 100 pieces of visual media were dubbed in Valencian, the variety spoken in the Autonomous Community of Valencia, and over a dozen in Balearic, spoken on the Balearic Islands.5 In November 2019, Netflix included for the very first time in its catalogue an anime series dubbed in Catalan, Sakura, la caçadora de cartes, which was a particularly well-known anime in Catalonia in the early 2000s.

It is important to note at this point that there is obviously not one element of culture that defines a nation, but that there are undoubtedly many key elements and key moments that enable the creation of an identity and a sense of togetherness. For many decades, the content children and teenagers could consume on TV was anime dubbed in Catalan, which marked their upbringing and defined what growing up in Catalonia in the 1990s and 2000s was like; an experience not shared with the rest of Spain.

1 Newhouse, John, “Europe’s Rising Regionalism”, in: FOreign Affairs 76/1 (1997), pp. 67-84, p.68.

2 Ibid., p.76

3 https://www.ccma.cat/tv3/Record-historic-de-les-campanades-de-TV3/noticia-arxiu/581820/

4 https://pandora.girona.cat/viewer.vm?id=758586&view=hemeroteca&lang=ca&page=39

5 https://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llista_d%27anime_en_catal%C3%A0

Show Comments

Sains Data

The influence of cultural exchange on identity formation cannot be underestimated, and this is especially evident in the intersection of Japanese culture and Catalan identity. The use of anime as a tool for self-expression and the creation of a shared cultural identity is a fascinating example of the power of popular culture in shaping our sense of self and belonging.

Comments are closed.