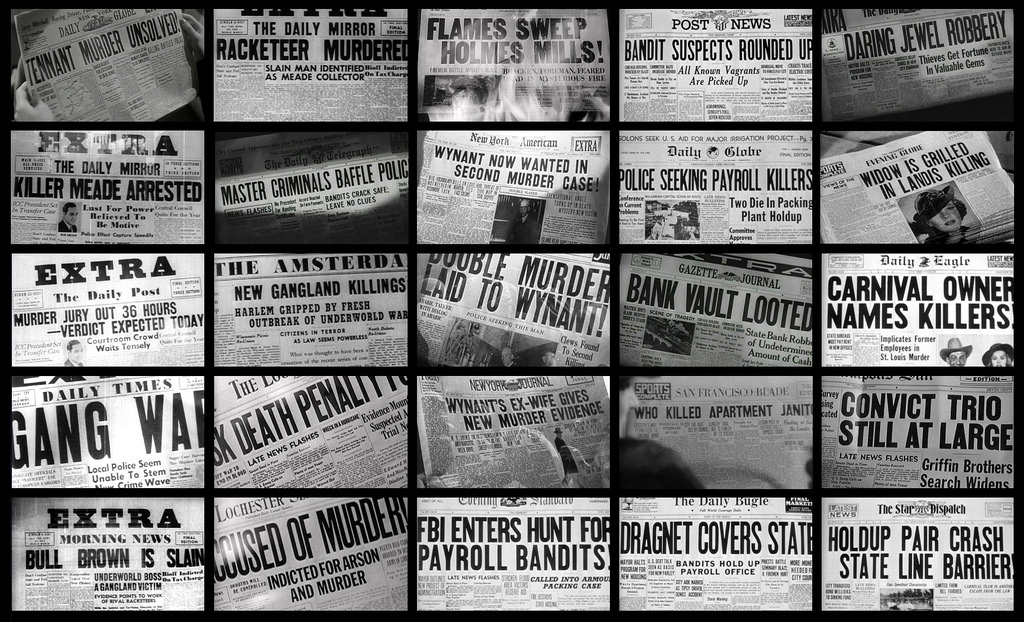

Social media and most media outlets allowing us access to more content and information than ever before has given us insight into tragedy all throughout the world. One could argue that it is in fact because of this swelling rise of information we have access to that tragedy seems to be all around, with online publications producing more articles than seemed possible and people sharing and tweeting articles of their experiences of tragedy amplifying this spread of information. Nevertheless, a question that a lot of academics have been worried about is how we report on tragedy and how one can ethically report on tragedy. Now by tragedy, whether it is an instance of domestic violence, such as the heart-breaking tale of Sara di Pietrantonio burned alive by her ex-boyfriend in Rome, or terrorist attacks such as the Brussels attack of 2016, we refer to a tragic event causing the death of one or multiple people that usually has somewhat of a political or social significance. How does one, then, react to tragedy, especially when it’s not one’s own?

Can’t tell people how to react

Paradoxically, my main advice would be that you cannot tell people how to react to tragedy; everyone reacts in their own manner. I realise how hypocritical this may seem given the title and purpose of this article, but what I aim to suggest is that you can’t dictate how people react to tragedy. After the Paris attacks of November 2015, where three suicide bombers struck near the Stade de France in Saint-Denis, followed by suicide bombings and mass-shootings at cafes, restaurants and the Bataclan theatre in central Paris, something that really perturbed me was the Facebook reaction. An aggressive finger pointing ensued. Social media was dominated by xenophobic and Islamophobic claims pointing to this ridiculous notion of an inherent ‘evil’ and ‘terrorist’ nature naturally linked to Islam – completely unfounded, dangerous and racist.

Europeans can no longer afford to turn a blind eye at the tragedies occuring outside of Fortress Europe.

On the other side of the spectrum was an aggressive search on who was really to blame and people started regurgitating millions of other tragedies that weren’t mourned for enough. Keyboard warriors that latch onto tragedy to make it into a social media political campaign or to amplify their opinions – remember that every tragedy causes victims, and one must learn to mourn together, and be mindful and respectful. Don’t get me wrong, I am not stating that you purge your political opinions when discussing such events, but I think, especially in media coverage, far too often we focus on an apparently black and white political argument and forget the human aspect of tragedy. Political debates are necessary, useful and constructive when they are not disparaging and do not incite hate.

Never Prioritise Suffering

Having said that, there is something we need to be especially mindful of. Now, I do scold the aggressive tone and being dictated how I should mourn for Paris or for Beirut, given that shortly before the aforementioned Paris attacks, ISIL also claimed responsibility for the two suicide combers that detonated explosives in Bourj el-Barajneh, a southern suburb of Beirut inhabited mostly by Shia Muslims. However, one can’t help but wonder why this other attack went by relatively unnoticed. This was one of the largest terrorist attacks to ever occur in Beirut, and seemed to slip largely under the radar given the predominance of media coverage on the Paris attacks. I don’t think we should weigh and compare tragedies as each tragedy stands on its own, with its complexities and repercussions. Without dictating how people should react to tragedy, and thus undermining people’s suffering, whether of a Parisian or Beirutian, we need to ask ourselves why this is. European media outlets need to cater to their European audiences, but by prioritising the suffering of ‘Europeans’ we are propagating a notion that Europe and the Middle East, or anywhere else in the world, are inherently different and mutually exclusive entities – which is certainly not the case. Moreover, the tiresome excuse that “they’re used to it over there” is derogatory, patronising and useless. Especially given the European complicity in the rise of ISIS and other Islamic fundamentalist terrorist groups, Europeans can no longer afford to turn a blind eye at the tragedies occurring outside of Fortress Europe. An important skill in being respectful when responding to tragedy, is learning to mourn for victims of suffering all over the world.

Empathy vs. Sympathy

How does one learn to mourn with victims of suffering? The problem of reacting to tragedy which has always troubled me is to what extent am I trying to be there for someone and to what extent am I just appropriating someone else’s cause? This is something I find especially important in the reporting on tragedy, to what extent are you an ally or someone who is at a distance reporting on this cause? Watching the below RSA animation by American scholar Brené Brown is something I always found really inspiring and enlightening.

The difference between sympathy and empathy, is that sympathy is the feeling of pity for someone else’s misfortunes, whilst empathy refers to the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person. Thus by being invited to feel sympathy one can feel detached from the matter at hand. Scholar Susan Sontag mentions that so far as we feel sympathy, we feel we are not accomplices to what caused the suffering. This thus creates a simplified representation of desperation, of which we are but witnesses to and maintain a distance from. By choosing feelings of empathy over sympathy we grow closer to understanding the mourning of others, and instead of appropriating it to aggressively champion a political cause, become an ally to lend a helping and understanding hand. This can particularly be seen in conflicting reports on tragedies in the refugee crisis, such as the drowning of the child Aylan Kurdi on the beaches of Turkey in 2015. Media reporting invited feelings of sympathy, but never empathy that could lead to any actual understanding of the complex reasons why such a tragedy could occur – such as a lack of policies ensuring the safety of refugees embarking on the perilous journey towards Europe.

The first thing that happens in a flood is that there is no more drinking water.

I recently attended a beautiful and inspiring talk organised by English PEN with English playwright David Hare and Italian investigative journalist Roberto Saviano. Saviano’s response when asked about what he thought about this increase in information on the media particularly struck me. He mentioned a Catalan proverb that the “first thing that happens in a flood is that there is no more drinking water” and went on to describe how apt this proverb is in describing this phenomenon because when there is so much information it becomes impossible to find any content worth consuming. He suggested that we need to take a step back and question all the sources, claiming that we need to break through the surface, and not fear complexity but rather take our time to judge our sources and what we will take to be as truth. I thought this could not have been more perfectly and beautifully put. Always question all representations of tragedy, even this article if you will, question everything and then come to your own conclusions. But never, ever, impose your opinions on others, because at the end of the day one must remember that where there is tragedy, there is great suffering and the grief and respecting of that grief surpasses everything.