For the first time since its inception, the European Union is seriously contemplating suspending a Member State’s voting rights. Not surprising for an institution that usually values consensus above all, the use of this Article 7 has been dubbed the ‘nuclear option’. To be used as a form of deterrence instead of an instrument.

Yet, developments in Eastern Europe over the last years, and especially Poland’s recent reforms to its media and judicial institutions, have caused anxiety for the Commission, Parliament and fellow Member States. It is, however, unclear whether the Union has the instruments, volition and power to answer to these rising illiberal tendencies among its members.

Law and Justice in the Constitutional Court

Decisions of the Polish government in the past year have brought on the recent talk of enforcing Article 7. Elected on a populist agenda of socio-economic reforms and social-conservatism, the Law and Justice party (abbreviated to PiS in Polish) formed a government in the fall of 2015. Combining a majority in the senate the following spring with the office of president, PiS holds an almost complete political grip on Poland. The only potential obstacle to carrying out sweeping reforms is the country’s Constitutional Court.

The Court is a powerful institution that can declare laws unconstitutional. Although acting independently, the 15 judges are nominated by representatives of the Sejm, the lower chamber. This allows the Court’s composition to become a highly partisan issue, like US Supreme Court nominations. Especially when extensive reforms and ideological differences are determining the political agenda.

This is exactly what happened in the aftermath of 2015 parliamentary elections.

The previous liberal pro-Western government party Civic Platform and PiS fought the nominations of the Court’s judges. Both tried to pass dubious laws to guarantee results in their favour, but PiS’ refusal to accept the legal nomination of three judges triggered an initial probe by a worried Commission in late 2015. For PiS these three judges were crucial to achieve a favourable majority on the bench. Faced with a clear political desire to neutralise opposition from the court, the fundamental EU principle of the rule of law was being trampled on.

Pushing Brussels towards the nuclear option

Fast-forward to December 2017, the Polish government has passed 13 questionable laws regarding judicial reforms. Over the course of the past two years, Poland’s PiS government has had multiple run-ins with the EU regarding its political agenda, the government’s tightening grip on the media, and its refusal to adhere to European agreements on refugees. As the Polish government has consistently ignored these alarmed signals, the Commission has now recommended that Member States issue a formal warning on Poland’s meddling with the rule of law. It is the first step towards stripping a Member of its voting rights.

Although this is still a very long way from suspending voting rights, it shows how worried the Commission is about the illiberal tendencies spreading through Eastern Europe. Besides Poland, democratic backsliding in Romania and Hungary have also caused headaches over the past few years. Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orban has even proclaimed to be in favour of an illiberal democracy. Such contempt for the core European values of democracy, liberalism, and the rule of law, as defined in the Copenhagen criteria – the entry requirements of the Union – would be expected to be met with a swift and clear rebuke, or even sanctions, from the EU. It should not be possible to digress from such fundamental values.

Yet, the Union finds it difficult to respond to these illiberal tendencies and instances of democratic backsliding. Romania and Hungary have had a slap on their fingers, but Orban’s central-right European party, one of the biggest in the EU Parliament, has up until quite recently closed ranks around the Hungarian Prime Minister. This leniency has made sanctions, or even speaking about Article 7 in the context of Hungary, impossible.

The interventionist approach – while flawed on many levels – that marked the response to the Eurocrisis and had many advocates to be integrated in some form or other in the EU’s economic institutions, is now nowhere to be seen. Economic interdependence seems more obvious than political intertwining. And indeed, only now that Europe’s sixth largest economy is showing these same illiberal tendencies do the Commission and Parliament pursue a clear response.

A political response to democratic backsliding

But that means entering uncharted waters. Article 7 has never been used before and its label as the ‘nuclear option’ does not contribute to supporting its actual use. With Euroscepticism on the rise across the continent, the EU is, furthermore, careful not be seen as overreaching. The backlash to the recent actions by the Commission already proves that it is grist to the mill of Eurosceptics, and not least to the governments of countries – like Poland and Hungary – who use the EU as an external evil in order to shore up their own popularity.

Moreover, Poland’s ally with illiberal tendencies, Hungary, has already made clear that it will veto any attempt to strip Poland from its voting rights. Effectively removing the one institutional stick the Commission had to beat with, under the guise of possible European political overreach.

Actual political overreach is, however, almost impossible to achieve for the Commission or the Council of Ministers. Article 7 only deals with voting rights of the Member State in question and was designed to limit the consequences of a rogue nation on other Members and EU proceedings. Although still significant, the stripping of voting rights does not change the internal political constellation of a Member State. Already in 1999, back when the article was conceived, Member States probably did not want the EU to meddle in their own political dealings – and not without good reason. Yet, as a consequence, and as illustrate the cases of Poland and Hungary, the EU has almost no tools to actively challenge a country’s internal political course when it clearly goes against the Union’s fundamental values.

This lays bare a fundamental question for the Union that has crept up over the last decade, and has been at the core European integration since the beginning. Is the European project solely one of economic integration or does it also entail political and social unification? Indeed, some may say that the one is not possible without the others.

A clear answer or even a meaningful discussion on the question is avoided. Yet, the big challenges that the Union has faced over the past years – the democratic deficit, Eurocrisis, refugees, Brexit, and now the rise of illiberal tendencies among member states – have shown that this question needs to be faced head on. Without a clear vision for the future of a united Europe, the current cooperation and constellation will become untenable fast.

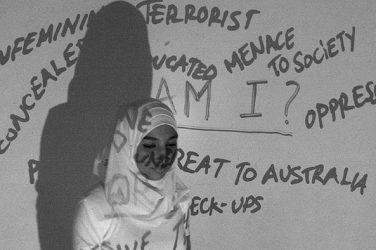

Cover Photo:Photo: Sakuto (Flickr); License: exactly what happened