While the new German government has just formed, the newly elected members of the parliament have already begun their work. With 735 members, the current Bundestag is the biggest ever – and it is also the youngest and most diverse. Malina Aniol had a look at all parliamentarians to better understand said diversity and see how well the Bundestag does in terms of minority representation.

An autumn Sunday morning in Berlin can take two forms: gloomy and grey streets empty as people are still recovering from the night before; or thriving, vibrant streets filled by markets, the last summer sun, and Müßiggänger (idlers who are taking life as easy as everyone wishes they could do themselves) philosophising in cafés.

The 26th of September was a Sunday of the latter, picturesque type. The only difference being that a notch more excitement and perhaps optimism for change was in the air and that, at certain corners, you could spot queues capturing whole building blocks. This Election Sunday seemed unique: for the first time in 16 years, Angela Merkel would not run, opening opportunities for all parties to start a reimagining of what Germany could look like. Within the immigrant community – or better immigrant communities as will later be explained – this also meant hope for better representation of their needs and realities in the parliament.

In recent years, the representation of people with a migration background – a uniquely German concept capturing both first and second generations of immigrants – has become a heated debate. An ever-growing number of voices demands a more diverse parliament – encapsulated in initiatives such as Brand New Bundestag (the spin-off of the American Brand New Congress). They are met by the argument that representation goes beyond having one specific identity feature and that an MP should have the ability to stand for universal representation.

Delving into this debate requires asking a fundamental question: What does true representation mean? And what should this core function of representative democracy look like in the real world? For this practical problem, it can be helpful to look at political philosophy, and Hanna Pitkin’s seminal distinction between descriptive and substantive representation.

Descriptive representation often addressed by pro-diversity groups evaluates how well the electorate resembles MPs identity characteristics. An overly simplified aim would be to create a mirror version of society in parliament guided by biographical and demographic traits such as age, gender or migration background. On the other hand, substantive representation looks at how well the elected stand up for the interests of their constituents without looking at the resemblance MPs have with the ones they represent. In reality, however, these two conceptions are not as clear-cut. Some evidence points towards a link between descriptive and substantive representation: an MP from a minority seems more likely to also substantially represent the needs of these constituents and further their interests. This cannot come as a complete surprise, as most would probably agree that while they have an ability to generalise beyond their own experiences, they would still assume that they know best what people with similar biographies want. Even if we disagree about the fine-tuning of it, there is an intuitive appeal to descriptive representation.

Listening to the people waiting in the seemingly never-ending lines to cast their vote, you will hear French or Turkish chatter or some Polish “dzień dobry”, greeting oncoming friends. Germany – even though its politicians for the longest time rejected this fact – is a multicultural state and a country of immigrants. But if we step through the looking glass not into the world of the Jabberwocky, but that of parliamentarians, will we be as surprised as Alice, or will we find a mirror image of German society with regards to migration background?

One year before the election, 21.9 million German inhabitants had a migration background – 26.7% of the population. This number has constantly been growing. When Merkel started her first term in office, only about 14 million people belonged to that category. One step behind the mirror, and we see a different world: 11.3% of the MPs now have a migration background. Too little? Back in 2013, the number was even lower, 5.9%. The new Bundestag is indeed the most diverse, at least concerning migration background, and still fails miserably to mirror German society in this regard.

One reason for this under-representation is the problem of curtailed voting rights and German citizenship law. Only one-third of the people with a migration background living in Germany are allowed to vote in the General Election. To be granted voting rights, you need to be naturalised (be a citizen), whereas at the local level at least all EU citizens are given the right to participate. Yet, until the turn of the millennium, it was nearly impossible to receive German citizenship without having “German blood”, meaning German ancestry. Only after a reform of citizenship law did immigrants living in Germany for long enough gain the opportunity to become naturalised. If the parliament should only represent those eligible to vote, the Bundestag comes close to a mirror image at the superficial level as 13% of all eligible voters have a migration background – leaving a gap of two percentage points. However, this narrow conception of representation would and does have far-reaching consequences for the quality of democracy and should not be adopted light-heartedly.

There are more shards to the mosaic of the broken mirror parliament than only the legal failures. And part of this puzzle can only be discovered when applying the lens of intersectionality, going beyond migration background. Germany is best known for its Turkish immigrant community: 2.8 million inhabitants have Turkish origins. If you drive through cities like Berlin or Cologne, their influence on urban life is clearly visible. Less visible in society is the second-largest community, people of Polish descent, with 2.2 million people. The numerous other, smaller communities that are hidden under the label “migration background” are even less visible. They often have different experiences and needs, while sharing the reality and problems constructed by the label “migration background” that is being put on them.

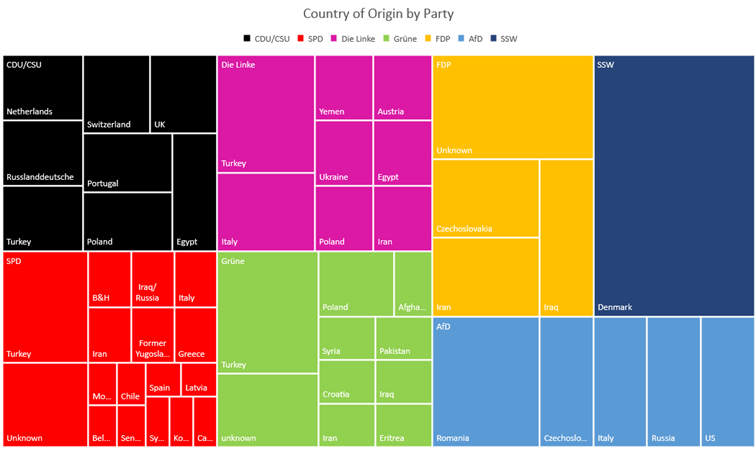

Taking a closer look at the representatives with a migration background in the new Bundestag reveals gross differences. MPs with Turkish origin make up 20.48% of those representatives, while only 4.82% of politicians with migration background are of Polish origin. In German society, people with a Turkish migration background make up about 13%. In short, among MPs with a migration background, the Turkish minority is descriptively overrepresented compared to an underrepresented Eastern European faction. However, in the parliament as a whole, both the Turkish and the Polish minority are underrepresented compared to the size of their communities in Germany.Explaining this divergence is a tricky task as research on this topic is still in its infancy and the process of candidate selection entails many different levels: from becoming a suitable candidate and intra-party selection to the ballot box. At each level, candidates with a migration background – no matter the country of origin – experience discrimination.

For many, the over-representation of the Turkish community might come as a surprise: Not only are Turkish immigrants and their children the more visible minority, but they are also known to be socio-economically less well off, and are associated (whether wrongly or rightfully) with Islam, which studies show is interpreted as non-German. All of these factors suggest a worse representation. Parties might be directly or indirectly discriminating against them, and thereby not nominate them as candidates. And at the final stage, the average German voter might also be less likely to vote for them even if they overcame all the other obstacles.

In contrast, the Polish community is barely visible, part of the dominant religion in Germany and socio-economically better off but still lagging behind non-migration background Germans. However, the picture is not that simple. Some point at a perceived higher assimilation of the Polish community – meaning that Polish Germans are less discernible in their ways of living from so-called ethnic Germans and thus also less aware of their group-identity – meaning that they are less risky for parties to put forward as candidates. However, research on ethnic Germans from Russia (Russlanddeutsche) calls this into question, showing that they experience similar exclusion and xenophobia although not racism from non-immigrants and have strong intra-group bounds. Furthermore, contrary to the above argument, higher group awareness and a clear distinction as an immigrant group under some circumstances can even be beneficial if a party has a progressive and multicultural electorate and wants to signal their diversity ambitions. Assimilation as an explanation remains inconclusive and seems far away from explaining the gross differences in representation.

An alternative line of thought could look into the differences in motivation and party engagement. Studies comparing the political participation of Russlanddeutsche – a proxy for Eastern Europeans – and Turks find that the latter are more active both at the formal level – elections – and especially the informal level – protest, signing petitions, or party work. This difference does not arise in a vacuum but is likely to have multiple causes, one of which is being addressed and animated by parties and thereby included in political life.

Generally, the Eastern European communities tended to vote for right-wing parties, especially the CDU. This can at least in part be explained by their communist history and a repulsion towards more left-leaning parties as well as an affinity for Christianity and a conservative value system. In contrast, the Turkish community classically votes for left-wing parties – especially the SPD. This might be motivated by perceived discrimination from right-wing parties and their cultural focus on immigration, but also by the link to the unions the Turkish Gastarbeiter often had.

Left-leaning parties with their focus on social justice and equality tend to foster migration background candidate promotion more. Knowing that they have a large Turkish electorate, they are also incentivised to have Turkish candidates. On the other hand, the incentives for the CDU and the other right-wing parties to promote Eastern European candidates are smaller, as less of them vote and their ideology is less focused on equality. In 2021, the SPD has not one successful Polish candidate, while the right-wing parties together have only one Turkish MP. The left-wing parties account for three quarters of the MPs with a migration background, while their share of seats in parliament is close to 50%.Representation goes beyond the looking glass: descriptive representation is only part of the solution to more substantive representation of all minorities in Germany. However, the link between both has been shown to matter. The first important lesson is that voting rights inequalities perpetuate the descriptive under-representation of everyone with a migration background. Only by making citizenship more accessible to all or expanding voting rights can society achieve a more inclusive and representative parliament. However, getting descriptive representation right is a messy process, with many intra-party obstacles that remain hidden from the outside onlooker. Analysing the output – the success of migration background candidates – reveals that we need to go beyond a simplistic understanding of representation.

While the label “migration background” might already create shared realities, the different immigrant communities have different needs and political interests not captured by this label. Germany, like Berlin’s Sunday streets, is diverse in some parts more than others. At the federal level, the representation of people with migration background has peaked not only historically but also compared to lower political spheres. A sign that progress is possible, while at the same time reminding us that democracy works at a slow pace. Representation matters, well-done representation even more, and the best of all representation – who knows what it looks like, we can only find out through discourse – is the mammoth task of our society.

Cover photo by Claudio Schwarz (Unsplash), Unsplash licence