E&M’s Oskar Cafuta hits us with a surprising story: Slovenian houses are too big apparently. Sounds weird? That’s what we thought. Yet, there’s a perfectly rational historical explanation. Read on to find about why many Slovenian families own a house that could home to three families rather than one – and why that truly is a problem for urban planners.

Housing crises are one of the biggest issues that cities and countries face today and it is no different in Slovenia. However, the housing crisis in Slovenia is twofold. This article seeks to explore the more unusual phenomena of Slovenia’s huge number of un(der)used and oversized houses in suburban and rural areas. Like many cities, Ljubljana has experienced a lack of affordable quality housing. However, while this of course presents a very problematic situation, Slovenia is battling the housing crisis on another front. In tandem with this lack of housing in the cities, there is also an excess of housing in other parts of the country.

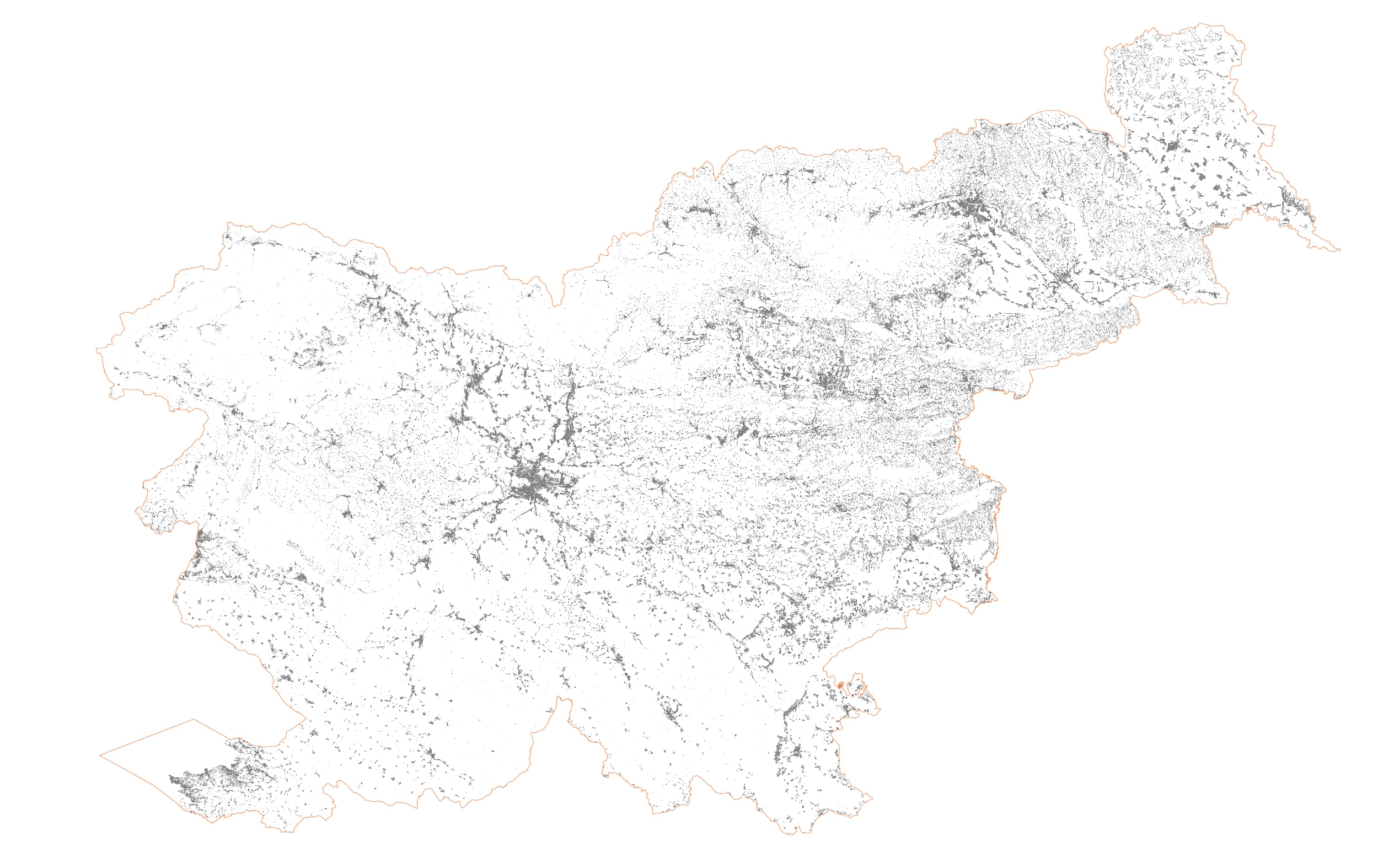

Just as the 1950s in the US brought “The American Dream House” typology of the suburban home with a white picket fence, garden, dog, swings, driveway and garage, the 1960s presented the time of “The Slovenian Dream House” typology. The Slovenian Dream, much like the American Dream, has always been a house in the suburbs or rural areas closer to nature. This has led to very dispersed building types which resulted in endless roads connecting single houses and increasing the use of personal vehicles. Over the years, the Slovenian countryside has lost its natural landscape due to oversaturated construction. Paradoxically, by moving to the countryside to be closer to precious nature, people started destroying the natural environment they wanted in the first place.

Socialism, despite being a time of conformity and strict regulations, brought quality architecture and urban planning to Slovenia

Building in rural and suburban areas is not exclusive to Slovenia; however how it is done, might be. At the end of the 60s, industrialisation was growing, new economic reform came into play, there was a boom in new, successful companies, stores started selling new, better things, people were earning more and a wave of optimism took over society. In Slovenia, particularly after World War Two, quick urbanisation occurred which increased the need for housing typologies that could be built quickly and provide sufficient standards. This was in the national interest, therefore important and skilled architects got tasked with the development of the new house types in cities. The results were innovative, well thought through house designs that provided good quality of life (even by today’s standards). Socialism, despite being a time of conformity and strict regulations, brought quality architecture and urban planning to Slovenia (Yugoslavia at the time).

However, the government could not provide housing fast enough to meet demands. Therefore they started easing the restrictions for private building and the private market, and loans became more accessible than ever before. This led to the loom of “self-construction”. The 1960s, 70s and 80s were a time when Slovenian dreams were becoming a reality.

New house types were born. The characteristically well designed typologies were replaced by standardised plans that were not intended to raise living standards but instead to provide for basic needs. The dream was to build a big house in the countryside for all generations of your family. Houses were usually built on the land that people inherited or were able to buy for an affordable price in the countryside which led to very dispersed settlements and visually continuously built landscape. There were three or four floor plans to choose from, all were very alike, often offering 250-300 square metres of space as they were adapted for big families. The thinking was “if we are building the house, we might as well build it big enough so our children and their children can live in it as well, thus saving them the trouble of having to build their own house”. The building process was also different. At the time, most people built their houses with their own hands and with the help of some friends.

After independence in 1991, the Slovenian landscape continued to change dramatically. The strictness of socialism was over and people were finally able to express their individuality however they wanted. The never particularly developed living and housing culture in Slovenia was getting worse. New extensions to existing big houses were built, facades were coloured in vivid colours, and new space partitions were added to existing houses to divide rooms into smaller living spaces with less natural light. People continued to make aesthetic changes to their homes, however they remained poorly insulated and inefficient to run.

As time passed, children moved out and built their own houses while parents were left with very oversized homes which elderly people cannot afford to maintain – and yet are too proud of to sell and downsize. According to the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (SURS), Slovenia is now left with 172,176 (out of 852,181 housing units total) empty housing units which is more than a fifth of all the homes in Slovenia. While 19,896 homes of the empty housing units are used as “second homes” or vacation apartments, there are still 152,280 housing units that are completely empty. Furthermore, 74,807 of housing units are inhabited by only one person that is 65 years old or older and 37,778 of those live in single family houses. As more than half of the empty homes are in the suburbs and rural areas, 68,436 empty homes are in the countryside.

Due to the expensive maintenance of big empty single and duplex houses, the majority of them are in poor condition and not achieving basic sustainability standards. While the number of newly built single houses in the suburbs and rural areas has decreased, it is not looking like it will stop any time soon. Despite having so many empty homes, new ones are being built, and even if the new built houses in the suburbs and rural areas are following all the sustainability principles with insulation and material choosing, a house of 300 square meters for a family of four in the middle of the countryside is not sustainable.

The issues arising related to this phenomena, however, are much wider and more complex. Slovenia is getting increasingly centralised with employment opportunities mainly in Ljubljana and a few other bigger cities, therefore daily migrations from the rural and suburban areas (where the big houses usually are) into the centre are rapidly increasing. Like other EU countries, Slovenia is pursuing national strategies and The Paris Agreement to tackle climate change and lower emissions, but it is being very incoherent about it. As public transportation is inadequate and not really developing, more and more roads are being planned. In April 2019, the Ministry of Infrastructure proposed an expansion of the highways leading to Ljubljana and a bypassing highway ring surrounding it with another lane in each direction. Thus, while other European countries are building and improving their public transportation infrastructure, closing and narrowing roads, increasing green belts to improve air quality as well as encourage healthy lifestyles and alternative forms of mobility, Slovenia is continuously increasing investments in roads and use of personal vehicles. With 541 cars per 1000 Slovenians, Slovenia is quickly becoming one of the most motorised countries in Europe.

So how can we get out of the paradoxical situation of spaces excess in times of its insufficiency? Cities such as Vienna, Zurich, Helsinki and other European cities have already developed successful strategies to tackle the housing crisis and improve liveability by building more affordable housing, increasing rent control, and improving public spaces by closing down roads and substituting them with quality public transportation in both urban and regional areas. Slovenia still has a lot to learn and adapt from other European countries in terms of creating better, more liveable cities. However, even if they achieved this, the substantial challenge of big empty houses in the countryside would remain and expand – especially as people would relocate into these cities with improved living conditions. This presents considerable concerns as well as exciting opportunities for future development. Slovenia is now at a crossroad and has to decide whether it will keep endorsing its poor living culture or follow the path set out by other European countries towards a more sustainable and liveable world.