Many people are unaware that the EU is increasingly involved in the South Caucasus through the Eastern Partnership Initiative. Is it worth the risk to to be drawn into a messy situation?

The South Caucasus is mostly known to a larger audience for this year’s Eurovision Song Contest, which will be hosted in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku. Many people are unaware that the EU is increasingly involved in this region through the Eastern Partnership Initiative (EaP). This intensified involvement is based on cultural, political and economic reasons. To give one example, the prospective construction of the Nabucco pipeline, a project aiming to make use of the natural gas reserves of the Caspian Sea, may decisively change the energy situation of European Union member states. But how fragile is this project when major regional conflicts are still unsolved? Is it worth the risk that the EU might be drawn into a messy situation?

Democratisation and integration

Since 2008, the EU has strongly emphasised the strategic importance of developing a close partnership with the South Caucasus countries Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia by establishing the Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative. About €310 million in funding was allocated to the three countries by the European Commission between 2007 and 2010. Primarily, this money is used to build up institutions aiming to enhance democracy, the rule of law and human rights. While democratic institutions in the Caucasus are less developed than in the former Central and Eastern European countries of the Eastern Bloc, ambition and efforts to strive for European standards in political and economic life certainly exist in this region on the edge of the European continent. There are however decisive differences among the partner countries. Georgia and Armenia are steadily ranked as “partly free” according to the Freedom House report Freedom in the World 2012 while Azerbaijan’s commitment to implementing democratic reforms is considerably lower, which is reflected in its ranking as “not free.” Besides these economic and political ties, the region is also connected to the EU on a cultural level. One obvious example for this cultural association is the countries’ participation in the Eurovision Song Contest for the last few years. The fact that Azerbaijan is even hosting this year’s contest should usually be a sign that European countries are taking part in a successful cultural exchange by peacefully competing against each other. Yet this particular event reveals one decisive regional obstacle among others that urgently demands solutions.

Unresolved conflicts

Armenia cancelled its participation in the song contest this year due to a major on-going political disagreement with its neighbour Azerbaijan. During an armed conflict from 1988 to 1994, the Armenian ethnic majority in Nagorno-Karabakh, which was part of the Azerbaijan SSR during the time of the Soviet Union, supported by the Republic of Armenia, tried to gain independence from Azerbaijan. After years of vast destruction, bloodshed and ethnic displacement, a ceasefire was established when Armenians gained the upper hand in the war.

As a result, the internationally unrecognised Nagorno-Karabakh Republic is de facto independent from the government in Baku. Since the highly unstable ceasefire in 1994, negotiations and talks led by the OSCE have not led to a solution that is acceptable to the parties involved. None of the questions in dispute, such as the status of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, the return of refugees and the settlement of borderlines, were solved. Moreover, violent incidents occurred along the border line in the recent years and antipathy between Armenia and Azerbaijan increased. The continuous armament in both countries demonstrates the explosive potential of this conflict. Similarly, in Georgia, the autonomous regions South Ossetia and Abkhazia have been demanding independence with Russian support. The war in August 2008 between Georgia and Russia showed that this supposedly frozen conflict can quickly turn into open hostility. As an outcome, both regions are more independent than they used to be before the war and Georgia struggles to maintain its full territorial integrity. Simultaneously, Georgia has undergone several years of cooperation with NATO, hereby aiming for full membership in order to solve its security dilemma. While membership in the next years is very unlikely, the involvement of the military alliance is also not able to solve the main problem of addressing the status of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. As a result, multilateral solutions that include all regional parties appear to be – comparable to the Nagorno-Karabakh case – far from achievable. The potential for an escalation of the conflicts in the Caucasus is obvious: why does the EU want to get involved?

A street sign on the way into the Nagorno-Karabakh territory as a sign of the unstable situation in the region: “Free Artsakh Welcomes You.”

Why care about your neighbour’s garden?

Despite the conflicts described here, several soft security challenges exist in the Caucasus region that can potentially affect European countries. After the demise of the Soviet Union, trafficking of arms, drugs and humans in the region has been steadily increasing. Because of their geographical location between Central Asia and Europe, the South Caucasus countries serve for instance as a route for opium from Afghanistan being transported to Europe. Moreover, Armenia and Azerbaijan both border on Iran and are therefore considered to be essential partners to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. International cooperation would allow the EU a greater leverage to handle these issues by enhancing the abilities of the local authorities and border control, hereby eventually benefiting Europe’s soft security.

Second, radical Islamic groups in the Caucasus represent an international threat. Even though this threat might be smaller than in other regions, the second Chechen war spread Islamic radicalism to the South Caucasus, mostly in the northern Sunni part of Azerbaijan. While the chance of any major ideologically led armed conflicts is rather low, the rise of radicalism increases the danger of terrorist attacks in Azerbaijan, which can also imperil energy transportation routes to the EU.

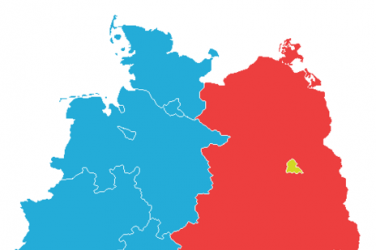

Geopolitical map of the Caucasus region.

These energy transportation routes mark the third and probably most decisive reason why the South Caucasus is of high interest for European countries. Due to Europe’s dependency on gas imports from Russia, the goal to diversify the origin of natural gas being sent to the EU has emerged as a top priority. Even though Russia remained a reliable energy supplier to its European partners so far, the great economic power that Russia can exercise by controlling a big part of European gas imports, drew politicians’ attention to the Caspian Sea. The Nabucco pipeline, stretching between Turkey and Austria, is one of the projects that should help with this diversification and the countries in the South Caucasus play an important role in this. One main gas supplier for this pipeline is Azerbaijan, which is expected to drill natural gas from the Caspian Sea and to transport it via an established pipeline through Georgia, connecting with Nabucco in Eastern Turkey. It is hoped that the maximum discharge of the pipeline will reach 31 billion cubic meters of gas, of which 8 billion are to be delivered from Azerbaijan with the potential of further expansion. When fully operating, Nabucco’s gas supply could reach about a quarter of current Russian gas exports to the EU. The pipeline construction is scheduled for 2013, with the first gas being delivered in 2017. There are, however, the critical voices of experts who, among other points, question the implementation of this project with regional conflicts being unsettled. While the South Caucasus is already related to Europe’s security and to the EU’s goal to promote good relations with its neighbours, the region will reach a higher level of importance if it becomes essential for energy security.

Europe’s strategic interests and our responsibility to contribute towards a peaceful future in this region are interrelated.

Turning away or intensifying efforts?

For European citizens the questions might arise: why should we get involved in such an unstable situation at all; why don’t we deal with other urgent issues instead of stepping into uncontrollable conflicts in the Caucasus? To answer this question, I would argue that Europe’s strategic interests and our responsibility to contribute towards a peaceful future in this region are interrelated. While there is obviously a risk connected with a stronger EU involvement in the South Caucasus, the reasons for a stronger involvement seem more important. First, Europe has major interests in the region. Second, it is important to point out that the complicated and unstable situation in the Caucasus region probably only has a chance of being resolved with the help of international parties. And Europe is already providing political answers to the regional challenges with the Eastern Partnership. The economic and social reforms that the EaP is carrying out must be accompanied by visions of how to provide peaceful solutions to these conflicts. Rather than turning away now, it is necessary for Europe to increase its efforts: Europe plays a special role in this situation since it is maintaining positive relations with all regional parties including Russia, hereby holding the opportunity to act as a mediator. Europe’s interest in friendly relations with its neighbours goes hand in hand with the necessity of taking on an important role in conflict resolution in the Caucasus. Third, the initial democratisation and the increasing role of civil society show that core European values are in the process of entering at least some South Caucasus countries. Neglecting rather than promoting this development could terminate this positive transition. It can’t be in our interests to disregard this responsibility.

Cover photo: sunriseOdyssey (Flickr); Licence: CC BY-SA 2.0