Peacekeepers, often called the blue helmets, are soldiers the UN deploys in post-conflict areas to monitor and “keep” peace. However, these peacekeepers are sometimes perpetrators of crimes themselves, especially of sexual abuse and exploitation, which target some of the most vulnerable parts of the local population. This begs the question: how come the ones sent to protect are the same ones that perpetrate violence? E&M’s author Francisca Rosales dives into the topic, looking at the roles of gender and power dynamics in this phenomenon.

Sexual abuse and violence perpetrated by peacekeepers

On a cold morning in March, I was listening to a podcast on Women’s Day, which sparked my interest in women’s roles in international relations and conflict settings. The podcast also focused on the fact that peacekeepers, the military personnel employed by the UN, often perpetrate sexual exploitation and abuse against local populations. This information seemed incredibly paradoxical to me, especially as these actions are the opposite of peacemaking or peacekeeping.

On the one hand, sexual violence is explained as a symptom of “militarized masculinity”. On the other, the UN often (mistakenly) expects women to be the solution for reversing toxic peacekeeping cultures, and thereby cases of sexual misconduct.

Like any puzzled social scientist, I decided to research why peacekeepers become perpetrators and the serious implication this has for local women and girls. After hours of research, I concluded that sexual violence perpetrated by peacekeepers is deeply linked to gendered dynamics. On the one hand, sexual violence is explained as a symptom of “militarized masculinity”. On the other, the UN often (mistakenly) expects women to be the solution for reversing toxic peacekeeping cultures, and thereby cases of sexual misconduct.

The idea that what happens in local settings matters for the international community is important for highlighting women’s roles during conflicts. Conflict and peacekeeping missions can be highly gendered contexts since gender norms shape one’s attitude. The concept of militarized masculinity highlights both the gender dynamics in highly masculine and militarized contexts, such as peacekeeping missions, and the masculine traits one acquires during military trainings along with their negative repercussions. The concept also highlights how imposing dominant forms of masculinity inevitably reduce feminine roles to an inferior status. The privileging of stereotypical masculine roles, such as violence, can lead to gendered tensions for male peacekeepers.

Peacekeeping operations do not solely have military responsibilities. They mostly entail humanitarian responsibilities such as organizing elections, ensuring compliance with human rights, and restoring the rule of law. Peacekeepers lack possibilities for engaging in open conflict, as peacekeepers can only recur to it in cases of self-defense. Feminist scholars have asserted that this non-emphasis on soldiering-related activities creates a masculinity crisis.

Sexual violence and abuse become a mechanism for peacekeepers to assert their heterosexuality, “satisfy their sex drive”, and take advantage of local women and girls who are in a vulnerable position.

This pushes men to reinforce their virility, triggering sexual violence. Sexual violence and abuse become a mechanism for peacekeepers to assert their heterosexuality, “satisfy their sex drive”, and take advantage of local women and girls who are in a vulnerable position. Thus, peacekeepers use situations of deprivation and unequal power relations to exploit local women. Many single mothers, orphans, and refugees are forced into having “survival sex”, a phenomenon where sexual assault is disguised as prostitution. Indeed, it is common to see peacekeepers impregnating underaged girls who exchange sex for food or money.

The UN’s response

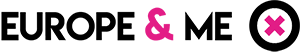

Faced with criticism from these harmful gender dynamics, the UN intervened to save its reputation. The solution for reversing the toxic “macho culture” in peacekeeping operations was (not surprisingly) to include more women as peacekeepers. At first, this does not seem like an irrational option. However, including women in peacekeeping missions to reverse militarized masculinity cultures seems paradoxical.

Feminist scholars suggest that the UN seems to have forgotten that gender is a social construct, where people are inevitably socialized into gendered roles. This became evident in a report published by Kathleen Jennings in 2008, which found that female peacekeepers are often unwilling to report their male colleagues in cases of misconduct. Therefore, including more women in peacekeeping missions to keep their male colleagues “in check” only reinforces the stereotype of women as motherly babysitters and disregards that women can be socialized into hyper military environments to “fit in”.

Gender parity between peacekeepers could genuinely work only in situations of 50/50 parity, and women peacekeepers are considered a valuable asset in missions. Gender violence practiced by UN employees would reduce as women are less prone to engage in prostitution and sexual violence compared to male peacekeepers. Also, the shrinking male-dominated context would tend to socialize women less into male-gendered roles.

The Case of MONUSCO in the DRC

This logic is mostly evident in MONUSCO, DRC’s UN peacekeeping mission. Since its beginning, the UN peacekeeping mission in DRC has had one of the highest rates of sexual exploitation and abuse compared to existing missions. Despite implementing strategies of gender mainstreaming and increasing the number of women peacekeepers, the number sexual allegations did not see a linear decrease. Thus, it remains to be seen whether SEA is eradicated when gender parity is truly achieved.

While sexual violence perpetrated by peacekeepers hired by the UN to protect populations in conflict settings is puzzling, the answer to the issue seems to become even more complex. While gender seems to explain a lot of power dynamics between men and women, we cannot forget that gender is not the sole determinant factor for human actions.

Intersectionality at the heart of the issue

Indeed, male peacekeepers abuse women because they are forced into gendered stereotypes as the “subservient” gender. However, this phenomenon also takes place because these local populations tend to be marginalized, racialized, and poor.

Gender relations in peacekeeping settings are intersectional. Indeed, male peacekeepers abuse women because they are forced into gendered stereotypes as the “subservient” gender. However, this phenomenon also takes place because these local populations tend to be marginalized, racialized, and poor. When a peacekeeper assaults a woman, he is also assaulting someone who is in a less-powerful position, not only because of their gender, but also due to the power dynamics between peacekeeper as the “savior” and “powerful” entity, and the victim in question as a destitute person due to the conflict and the political, social and economic violence that is present.

By focusing on gender as the sole explanatory variable we will keep on placing women in a weaker position. And society will continue to “justify” sexual violence on the grounds that military setting settings foster the idea that “boys will be boys”.

What happens in the local context matters with regards to how we should arrange international politics, including peacekeeping operations. As Enloe, a feminist scholar, argued, “there is nothing inherent in [peacekeeping missions] that makes soldiers immune to the sort of sexism that has fueled military prostitution in wartime and peacetime”. Therefore, it is incorrect to leave gender dynamics unmentioned when we study conflict, gender relations, and sexual misconduct. However, we cannot forget the challenging task of how to frame the issue of sexual violence. While gender theories partly explain episodes of sexual misconduct, the issue is more multifaceted and intersectional.

Picture by Imprensa AgruBan® on Pexels.