The second part of Christian Diemer‘s series On the Brink takes us to the heart of celebrations for the Ukrainian national holiday in L’viv. With Ukrainian patriotism stronger than ever, Christian is surprised to find himself at a muted and pensive Independence Day party…

A silent commemoration

A large map of Ukraine welcomes the newcomer at L’viv’s train station: “Plan-scheme of the railway connections of Ukraine”. The map, framed by majestic Corinthian columns and pillars, is lit up sharply by a flickering advertisement on the neighbouring wall. However, recent events are not reflected within it. The tangle of orange lines still interweaves with Crimea. Luhans’k and Donetsk in the east appear as well-connected as Uzhhorod and Chernivtsi in the west. And yet the map, lit up and down over and over again, does appear in a different light. Red digits over the station entrance display the date: 24.8. Ukraine is to celebrate the 23rd anniversary of its independence from Russia. Or rather, it isn’t…

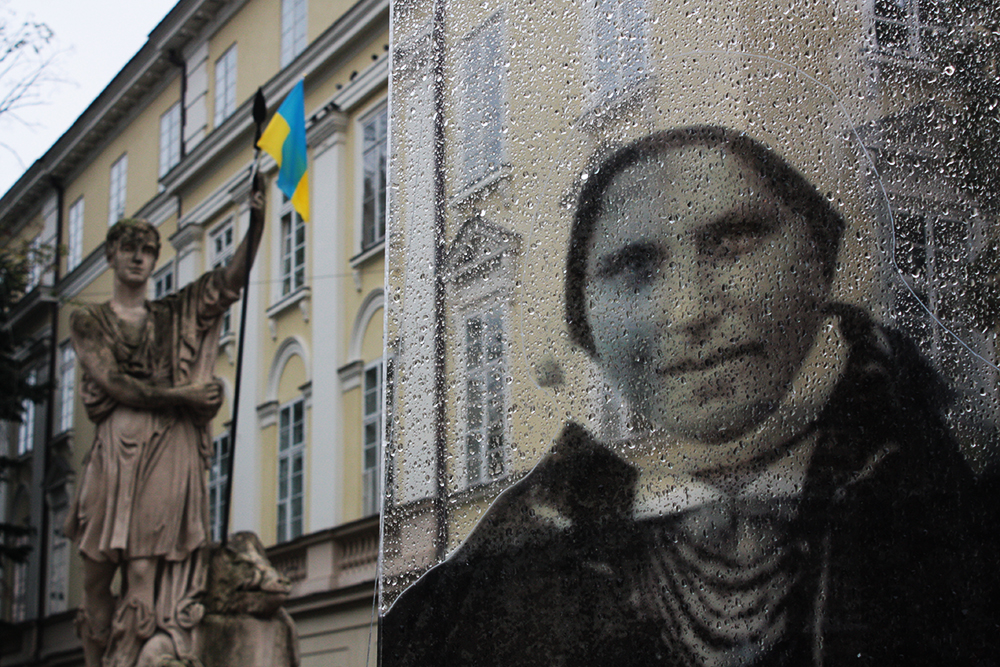

Pre-autumnal rain is drizzling, the morning passers-by walk around busily, sleepily. If it were not for the hundreds of blue and yellow flags that can be found on almost every building and car, one would hardly notice the national holiday. Even in the centre, where I seek shelter from the rain in a tasteful, Viennese-style coffee house, there is not a lot to be seen. In one corner of the Ploshcha Rynok [market square], there is an art installation made from rectangular glass panes: historic photographs of Hutsul people layered over UNESCO-listed façades, washed-out memories of an ephemeral yet subconsciously manifest past. In front of the Adonis fountain, a man with a Cossack plaid proudly poses for his friend’s camera. Some people walk around with flags or blue and yellow ribbons, dressed in vyshyvanki, traditional embroidered clothing. “It is still early,” apologises a passer-by. “And it’s raining.”

Ukraine is to celebrate the 23rd anniversary of its independence from Russia. Or rather, it isn’t…

During last year’s national holiday, the Rynok was dominated by a massive stage, music of all sorts and genres was blasted into all corners of the city centre. Seemingly each and every children’s dance collective from the region presented lovingly redundant choreographies of Ukrainian folklore set to shrieking loudspeaker music. Fourteen-year-old popstars-in-waiting luxuriated in pompous pop ballades or Rammstein-esque covers of age-old Ukrainian tunes. In full regalia, traditional songs were celebrated, a Canadian-Ukrainian folklore choir made its appearance with a large piece of traditional bread. This year there is not even a stage – all just because of a bit of rain? The answers come straight and logically: “There’s a war going on in the east.”

The complete absence of music subtly shadows everything, leaving an eerie sense of something fundamental missing, or yet to come. And nevertheless, there are plenty of sounds to observe. A symphony of bells is ringing and clinking from the towers around. Reverent, ardent chorales resound from the inside of the churches, as people and incense stream in and out. The tramway hisses angrily. Every now and then, a Slava Ukrayini! Glory to Ukraine! echoes over, answered by a Heroyam slava! Glory to the heroes!

Doll yourself up, pose and give putin a good kicking

On the Rynok, trams from different eras are exhibited in a row, open to visitors. Cossacks with machine guns pose with girls, some of whom have Ukrainian flags drawn on their cheeks or on their earrings. Most have opted for blue and yellow. A few have blue and yellow on one cheek, red and black on the other. The latter were the colours of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, active between 1943 and the mid-1950s, which collaborated with Nazi Germany in hope of gaining an independent Ukrainian national state, before fighting and losing against both Germany and the Soviet Union. A bulky man wears a T-shirt bearing the words Putin khuylo – Putin dickface. In front of the town hall, a wall of photos commemorates those who have fallen at the eastern front.

“Davay, kick Putin’s arse!”

On Prospekt Svobody, the magnificent tree-lined boulevard built over what was once a river, blue and yellow flowers form the Ukrainian flag. At the bottom of the statue of national poet-hero Taras Shevchenko, long-legged beauties pose in evening dress. Opposite them, a tent has been set up to inform people about the front and invite them to make a donation. Venerable men in their Sunday suits heatedly dispute the situation in the east. I recognise some of them as having bawled out fervent patriotic songs in the same place one evening over a year ago.

Next to the Shevchenko monument, the youth branch of the Svoboda party has a placard: another map of Ukraine, with a hole in it. People can stand behind it and lend their faces to a figure with a machine gun in his hands, kicking eastwards, where a clumsy Putin, both hands forward, flies out of the country in a high arc. It is the attraction of the avenue. Passers-by burst into laughter. Parents encourage their children, “Davay, let’s go and shoot Putin”. Fathers hold the little ones up so that their faces reach the height of the hole in the placard. Young girls retouch their make-up, pose lasciviously, stick out their tongues in disgust, freeze with angry expressions looking east.

Singing prohibited. Ukraine is at war.

A silent national holiday without music – and yet not completely without it. Just before 3 pm people gather for the national anthem; “everywhere”, as the announcement has it. The bells strike three. The trumpet players on the town hall tower blow their hourly fanfare. Minutes pass. The first start to sing, others gather around, the crowds get moving, the chorus emerges. But the hymn seems more like a warm-up for the shouts that follow, starting all over again and again: Slava Ukrayini! – Heroyam slava! Slava Natsii! Glory to the nation! Ukrayina! Ukraine! Girls experiment with throwing a meagre Slava Ukrayini into the crowd that echoes back as a thundering Heroyam Slava!

The national anthem, once more. And then something magical happens. People just go on singing. Some have a songbook. The old remember the words anyway. Some have tears in their eyes. If a branch of folk music has grasped the raging, unquenchable sadness and joy of life, of a people as sad and joyful as this, it must be that of Ukraine.

The singing gets more boisterous, a song about a fickle girl and her long-suffering suitor: on Monday she told him they would gather periwinkles together, he was there, she was not, she tricked him, she let him down; on Tuesday she told him that she would kiss him forty times, he was there… They get as far as Friday before a woman interrupts: “There are people dying in the east!” The singers break off. A man with a songbook commemorates the brothers and sisters who have died at the front. Minutes of silence on the square.

Internal Music

And then on it goes, all over again. It seems as though once the spell is broken, music starts to effervesce out of people’s souls, no longer able to be contained. The singing eventually peters out. But just one corner along, two street musicians perform polkas. At the Neptune fountain, three youngsters play rock music, hardly audible without electronic reinforcement. A young girl in a short skirt, entirely covered by a Ukrainian flag, ostentatiously delivers bank note after bank note to the drummer.

Even the obligatory drunkard is there: tall, wiry, red-skinned, utterly sloshed, daring, enchanted. In the middle of the assembly, he lies down on the pavement, throwing kisses and grenades that only he can see, crawling through imaginary trenches and under girls’ skirts. A huge Ukrainian flag in his hands, the black and red Ukrainian coat of arms on his T-shirt, he howls unintelligible things, eyes twinkling, with a monstrous voice that sends shivers down the spine.

Side streets. School boys play metal on three violins. In the Armenian district, a band plays country music. Girls wave and laugh flirtily. A big band has installed itself on the market square.

The rain has stopped, the setting sun imbues the clouds with a rosy aura. The silent independence day fades garrulously.