Our E&M author Nisa Sherifi found herself face to face with an ingrained and structural toxic masculinity – in the strangest of places: in a sandbox where children played.

A job with good intentions

This summer, after graduating from my master’s during this getting-a-bit-old pandemic, I flew home so I could get away from the 22 m² student dorm studio, where I had spent uncountable hours learning international law and critical theory.

When I came back, I began babysitting the children of my landlords for the summer. The job was clear: activities with the kids, no more than one hour of TV time, and speaking to them in Albanian (the language of the father, a friend and compatriot of mine). Naturally, after over a year of confinements and inside activities, both me and the kids seized every opportunity we could to go to the park.

I babysat 3 kids – the oldest is a boy, and the two younger ones are girls. All three – extremely smart, cute, and well-behaved. When the siblings played or interacted, I’d get the impression that the older sister was more patient and gentler with the toddler than the older brother. Despite confirmation from their mom that indeed the son was more adamant about his own wishes and that the middle daughter was always trying to include and consider her younger sister, I still thought that maybe I was reading too much into it, and that the way we are socialised in gender binaries does not manifest itself so clearly in kids that are 2.5, 5 and 8 years old. The parents make sure that the kids don’t get gendered differential treatment, so I thought that perhaps it was a professional/academic bias that had pushed me to see these subtleties.

Yet, reality soon found a way to put an end to my self-gaslighting and open a box of complex and puzzling questions.

Mr. Tinyman and the roots of toxic masculinity

When September came around, the older siblings started going to school and to their extra-curricular activities, leaving me to babysit the cutest croissant-toddler in existence, maybe the cutest there ever was an will be. She is a toddler of few words, high skepticism, and full autonomy (or as full autonomy as a 2.5-year-old can achieve). Although shy around others, she knows what she wants and expresses it insistently.

One day, we decide to go to the park. We get to the park, and my toddler chooses her favourite place to play in the beginning – the sandbox. Mind you, this is a consistent choice. Whenever we go to the park, especially alone, the sandbox is the first place she chooses to play. I think it’s because she likes to slowly warm-up to new places and people, and in the sandbox she has the autonomy to do as she pleases with her time and toys. “Do you want to play together?” I ask. “No” she politely replies, and so I leave her to play alone, because it’s never too early for a little girl to understand that her consent matters everywhere and all the time. I come from a culture where a toddler’s consent is ignored in many, if not most, contexts. Being a rather friendly people, it is common for random strangers on the street to kiss and hug random strangers’ children, and if the child turns their head around or tries to struggle against the uninvited affection of an unknown adult, they are simply ignored. Luckily, the parents of the toddler do not abide by this, and make sure her wishes to not be touched or interfered with are respected. But parents aren’t omnipresent, and neither are feminist babysitters, I soon found out.

After she started constructing her sandcastles and mansions, I decided that I should probably do the same. You know, just to unwind. After all, there is a reason sandboxes are present in many therapists’ offices. So, we both build our creations in peace for a while.

Enter Tinyman (this will be his official nickname for the rest of this article, and its relevance will hopefully become clear soon). He is about 2 or 3, so roughly the same age and size as my toddler, and he is going around doing his thing in the sandbox—or so I thought. Eventually, he comes up to me, and points at the feeble castle I’ve attempted to make. I smile and reassure him that, yes, it is a sandcastle. He points at it again, so I reconfirm it’s a sandcastle, and ask him if he wants to sit down and build with me. He grabs a tiny shovel, “cute”, I think, “he just wants to play”. Except he doesn’t. He proceeds to ram the tiny shovel into my sandcastle, hitting it over and over, until he has made sure the entire thing is flattened. “What the fuck? That’s rude” I’m thinking, but obviously not saying that out loud. I look over at his grandma, who giggles and says that he is known to often “play in a tough manner”. She doesn’t explain to him that he shouldn’t do that, in fact, his destructive behaviour, no matter how trivial, doesn’t seem to bother her at all. It appears that to her, it’s “normal”. He wanders off from the pile of sand that once was my shabby castle, and of course I force myself to stop thinking about it because making a deal out of a toddler ruining my sandcastle is just weird, even if I’d try to explain that I think it’s the pattern of destructive behaviour and impunity that is problematic. Plus, it’s not the young babysitter of another toddler, with strong feminist convictions and no children, that is going to “educate their child”. So, as a good member of our current society, I let it go.

But, it’s as if this 3 year-old was sent to prove something about how the theory I’d learned was grounded in reality.

My toddler decides she needs a change of scenery and activity, so she goes to play with some bigger toys that are installed in the center of the sandbox. Not wanting to be an overprotective or overbearing babysitter, I stay at my spot, which is some 10 meters away. Time passes as my toddler is filling the toys with sand, and then emptying them again, engaged in the first steps of some sort of impressive construction project, I’m sure. But, at one point when I look over again, I see the face. “Is she crying?” I think. As I stand up to walk over to her, I see Mr. Tinyman is in front of her, and with every step I take her piercing screaming becomes louder. Obviously, I run over to ask what happened. She keeps scream-crying, so I ask her if he hurt her or hit her, to which she replies yes. “You hit her? You don’t have any right to touch her or hurt her!” I say to Mr. Tinyman, who seems baffled by my scolding tone. Next, I have to make sure my toddler feels safe, so I ask her if she wants a hug, and for me to pick her up and take her out of there. She nods, continuing her crying. Meanwhile, the grandma gets up and asks me if he hit her. I confirm that, and she proceeds to say how she’s sorry, how he sometimes does that, and how “you know, kids” – all like it was a rehearsed or recurrent script. To calm my toddler down, I offer her snacks, which makes me think of a thousand possible implications. Am I teaching her to resort to food whenever she feels down? What if she develops a weird relationship with food and snacks because of this? Should I talk to her about reaching out for help if she’s in a situation like this? Is this the right time? When is the right time? While I’m pondering these questions and holding a 2.5-year-old who’s stopped crying to be able to have her fruit juice and madeleine, I also observe Mr. Tinyman. His grandma’s words seem to have left little trace on him as he continues to wander around the sandbox. What I observe next is what scares me the most.

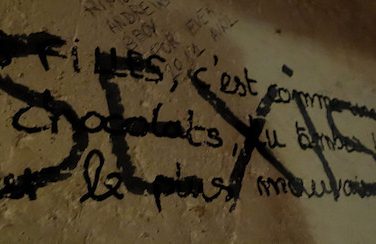

Mr. Tinyman proceeds to destroy the sandcastle of another girl, snatches the toys away from another one, and pushes a third one. Meanwhile, whenever he approaches boys, be they his age and size, smaller or bigger, he does not exhibit any hostile behaviour. For the most part, he observes them or tries to integrate their game calmly and progressively. Experts say children can recognise gender and gendered behaviour as early as the age of 3. In a world where violence against women and girls is normalised, where their consent is consistently ignored, even a 3-year-old has come to the conclusion that he can hurt girls, destroy their things, and face almost no repercussions, but that he cannot do the same to boys. It might be fear that is holding him back, because we already know women are socialised to be non-violent, while violence and “toughness” is encouraged in men and boys. He has the audacity, because he has the power, and in his still-developing brain, a gendered, scary, and potentially dangerous mindset has already formed. And it isn’t his fault, of course. He is 3. But it also isn’t very possible to intervene in how his family raises him, or to be omnipresent in the spaces where children continue to socialise with whatever norms they have been given. So, he will grow up, and if we don’t begin taking this kind of socialisation seriously, he will grow up with this implicit idea.

Changing the way men are socialised

While we are busy (forced into) having conversations about “not all men”, new generations of men are being born and raised with the same norms, same biases, reproducing the same power dynamics. My generation is not the one who is even having kids yet, and we aren’t even at the point where we can have a conversation about masculinity and how traditional understanding of masculinity is harmful for everyone. This 3-year-old then is likely not to be part of the last generation which will conclude that women are inferior by that tender age. Not unless we do something, and that something is having the right conversations so we can take the right actions. It is talking about structural violence, about norms, about implicit biases, about things like mental load and not getting personally offended and skewing the conversation to a land of ego-inflated defensiveness. This conversation is never about “good men”, who aren’t like “those men”, therefore “not all men”. This tiny kid is not evil, and I doubt his family is trying to raise a toxic man. The problem is not individual, is not him – it’s structural. It is also not you, in case you got defensive or annoyed reading this.

As a woman, I want a better and safer now and future for all women (and other vulnerable/marginalised groups) who are at disproportionally higher risk of being harassed, aggressed, raped or killed. As a babysitter, I want my toddler to be safer in the sandbox, and I want to know that if there is anything that happens, it truly is because children are children, and not because a child has already been socialised to recognise and act upon hierarchies. But, if the problem is structural and starts at home, then how can it be addressed? Raising our children “right” (read not in gendered ways) is not enough since we are not the majority and raising others’ children is impossible for an array of reasons. So, we need laws to protect us more, until the laws become norms. Because we need all the institutional apparatus of states to back us up, starting from schools and kindergartens.

Show Comments

Çiki

Very interesting and well written article. Were you thinking about your boyfriend while writing the second to last paragraph haha?

Comments are closed.