Why and how to include future generations in EU decision-making procedures?

Considering an accelerating climate crisis which causes long-lasting environmental damages and immense welfare spending, should future generations get a say in decision-making processes of the EU? The answer seems obvious: yes! The next generations should be included in democratic procedures, since it is them who will be severely affected by the choices we are making today.

How would the inclusion of future generations look like? Given that future people can’t simply show up and vote, a variety of institutional options to ensure their representation in democracy have been proposed. In Israel, Hungary and Wales some have even been implemented. These three countries introduced independent offices for future generations as a third institutional form to represent future interests. The institutions are charged with overseeing decision-making in parliament and the executive, especially with respect to environmental matters, and are typically staffed with trained experts.

Another way of including the interests of future generations has been to enshrine principles that protect future people in the constitution. This way, courts that safeguard compliance with the law would also ensure the rights of future people are respected. Finally, a popular suggestion has also been to include future generations in parliament, either by reserving seats for specialised representatives, establishing special parliamentary committees or introducing youth quotas so that young people may vote on behalf of future generations. In short, many options for representing future generations in democratic decision-making exist.

However, before we debate the most suitable ways to ensure that voices of future people are heard, we need to ask ourselves if doing so is really a desirable goal. After all, changing the political system might have severe and far reaching consequences. A decision of such degree merits closer investigation.

Is it desirable to include the future generation?

Currently, the default answer in most European countries seems to be in the negative. Hence, it is up to proponents of the idea to convince the public of the opposite. Some attempts at doing so have already been made. Most of them, however, are not very convincing. They usually identify some broader goal, such as fighting climate change, reducing public debt or promoting inter-generational justice, to then argue that including future people in the democratic processes would be a way of implementing the goal in question. For instance, proponents of environmental protection argue that future people should get a say in politics because this serves the higher ideal of fighting climate change. Their political engagement is thus a means to another end. While the ends may, of course, differ, the structure of such arguments is similar: they defend a particular goal and then argue that including future generations in democratic decision-making will help to achieve this goal.

the point of letting people vote is that we generally believe that it is up to the public to decide what a ‘just policy’ is

The problem with this strategy is that giving future generations a voice is purely instrumental. This tactic is objectionable, even though the end result may be just, since altering the democratic process for the sake of promoting certain desirable outcomes is problematic. After all, the point of letting people vote is that we generally believe that it is up to the public to decide what a ‘just policy’ is, recognising this as the most adequate way to determining what exactly a desirable outcome would include. If, on the other hand, one is certain to know the right choice of policy for ensuring environmental protection, why let anyone vote on them the wrong way?

What does democracy say about future generations?

A more promising approach to defend the inclusion of future generations in decision-making thus follows a different strategy. According to this argument, including future generations in the demos (the people who will get a say in decision-making) is necessary to live up to the principles inherent to democracy. The idea here is that democracy implies that (representatives of) all affected parties should participate in deliberation and decision-making. Since future generations are affected by a number of democratic decisions, they should be represented in democracy (at least in these decisions). Hence, giving future people a voice is not a means to some contended end, but a goal in itself because democratic standards require us to do so.

Here, one might question whether democratic theory does actually have anything to say about who should participate in the decision-making process. At first sight, it seems as if it does not. This is because it simply seems incoherent to constitute the demos through a vote among voters who would be entitled to vote only by virtue of the outcome of that very vote. An analogous case would be to let a champion of a tournament decide on who won the contest. Doing so would be logically impossible, since it involves an obvious circularity where who should be making a decision only becomes apparent after the decision has been taken. It follows that this “boundary problem” of the demos cannot be solved by appeal to democratic theory.

However, this is too hasty a response. While democratic procedure is inept in determining the boundary of the demos, democratic theory being comprised of underlying values, such as political equality and the right to self-termination, is not. The point is that our understanding of what constitutes democracy today includes not only procedure, but is rather characterised by a commitment to the principle of political equality among others. Refuting this would mean that political entities which deny voting rights to minorities, women or other groups of the population could still be classified as democracies, provided the ruling group follows democratic procedure in their decision-making. It follows that some principle internal to democracy exists that influences the standards according to which a demos needs to be defined for it to be labelled ‘democratic’. This principle is political equality. Hence, democratic theory can be employed to guide our answer to the “boundary problem”.

‘Being affected’ = required inclusion?

But what exactly does democratic theory have to say? The argument for the inclusion of future generations in decision-making suggests that ‘being affected’ should serve as a criterion for inclusion in the demos. In other words, the people that are relevantly affected by a decision ought to have influence over it. This “All-Affected Principle” seems to have intuitive appeal as a “government by the governed”.

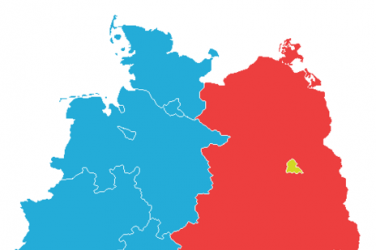

Today, however, “being affected” is understood only in legal terms. Suppose a farmer in Southern Germany was to use genetically modified plants that bring about the extinction of domestic plants and whose seeds are carried over long distances by wind, birds and insects. The farmers in Austria would be severely affected by this contamination of surrounding fields, as nature tends not to stop at state borders. Yet, because Austrian farmers are not forced to comply with Germany’s law, as the criteria for inclusion according to today’s version of the “All-Affected Principle” requires, they should not have a say in the decisions possibly affecting their very livelihood. People in Berlin, Hamburg and Frankfurt, who will most likely not be as directly affected as those Austrian farmers, on the other hand, will be included in the decision-making group. This result seems to be in contrast to the intuitive appeal of the All-Affected Principle. In fact, I would argue that what makes the All-Affected Principle so attractive is that it can account for contemporary political challenges of an interconnected world a lot better than a more traditional interpretation of the demos, which equates residency (and thus legal coercion) with the political right of participation.

My interpretation of the All-Affected Principle, which recognises the fact that different political decisions are likely to affect different people and that as a result the demos will vary depending on the decision being made therefore offers the most convincing answer to the boundary problem. According to this view, only those who will be significantly affected and cannot reasonably be expected to avoid the consequences of decisions made by the demos should be included in the decision-making group. This means that depending on the particular policy in question, various different constituencies (local, regional, national and global) may be perceived as most appropriate. Such an interpretation of the principle offers some degree of flexibility as to amending the demos in accordance with the decisions being discussed. People’s power over a decision should be proportional to how each individual’s relevant interests are affected by the decision. In other words, how much power you should have depends on how strongly the decision will impact you.

To approximate this, one could imagine a federal system, in which different policy areas are delegated to different government levels according to their typical impact/effect, so as to avoid having to decide on the constitution of the demos every time anew. A decision that is likely to affect people beyond political borders, like the one about introducing genetically modified plants, should therefore be deliberated by all those who will likely be significantly affected and cannot reasonably be expected to avoid the consequences of the new policy. This interpretation of the All-Affected Principle thus manages to strike a balance between including those in the demos that will be severely influenced by a policy and excluding those from the deliberation process that can reasonably avoid the impact. Since this interpretation of the All-Affected Principle is coherent, we can thus accept the first part of the argument for the inclusion of future generations in decision-making: Democracy does imply that (representatives of) all significantly affected parties, who cannot reasonably be expected to avoid the consequences of a decision, should participate in the deliberation and decision-making of the latter.

How much are future generations affected?

Here the answer is rather obvious: we harm future people in fundamental ways as a result of the climate crisis and thus severely affect them in a negative way. Droughts, flooding, desertification and many more life-hostile developments that come along with a changing climate clearly impact the fundamental freedoms of future people. Since decisions made by democratic governments to subsidise coal and fossil fuels, cut down trees, support factory farming and so on are causes of climate change, they can be said to significantly affect future people. Moreover, those living after us cannot reasonably be expected to avoid the consequences of these decisions, for even if we stopped emitting greenhouse gases today, global warming would continue to happen for at least several more decades, if not centuries. Since the climate crisis is just one of many obstacles that will affect future generations, it seems safe to say that future people should be included in decision-making in the EU and its member states, because the generations to come are severely affected by policy choices made today.