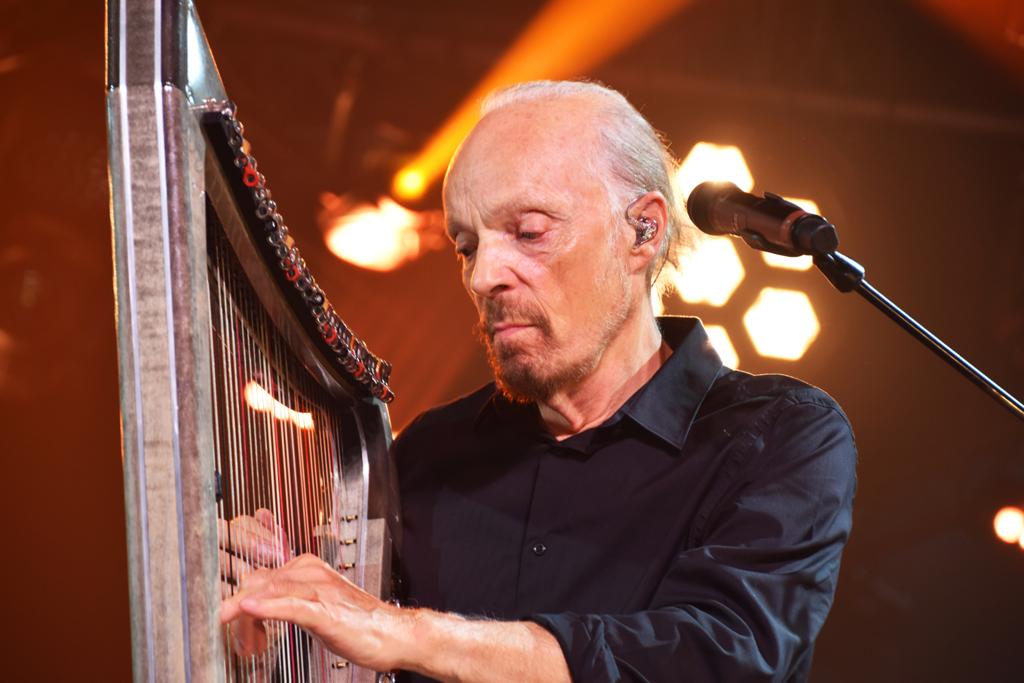

Alan Stivell is a French, Breton and Celtic musician and singer, songwriter, recording artist, and master of the Celtic harp. From the early 1970s, he revived global interest in the Celtic (specifically Breton) harp and Celtic music as part of world music. As a bagpiper and bombard player, he modernized traditional Breton music and singing in the Breton language. A precursor of Celtic rock, he is inspired by the union of the Celtic cultures and is a keeper of the Breton culture.

Note from the Salomé: When interviewing Alan, I witnessed his profound passion for Celtic culture and his boundless curiosity for cultures and creativity worldwide. His humble and ecstatic personality is both captivating and inspiring. Thank you Alan, for this interview.

Salomé: For you, what does it mean to be a Breton?

Alan Stivell: I think that the nuance of certain words in Breton language gives a sharper answer to this question than in French or in English. We have at least two words suggesting two approaches of identity: ‘Breizhad’ means citizen or inhabitant of Brittany, when ‘Breton’ speaks of the Breton people sharing an origin and certain cultural aspects. ‘Brezhoneger’ is a word used to refer to a Breton speaker, but nowadays the majority of people living in Brittany do not speak Breton anymore. I have observed that most French and English speakers are not conscious that Brittany is another Celtic nation. When people look at Brittany, they think of it through the French prism.

Salomé: Can you please tell us about the beginning and the unfolding of your career?

Alan Stivell: We owe the rebirth of the Celtic harp in Brittany to my father – Georges Cochevelou. Breton romantic poets spoke of harps rather than a lyre. The harp of the bards can have a barbaric connotation which can be fascinating. In 1953, I was a young boy of just nice years old playing the strings of the first Breton harp of the Twentieth century. The beauty of that carved harp and its Stradivarius angels’ sound have won people’s hearts from all over. Back then, I was already performing in various different places: Vannes-Gwened’s cathedral, Unesco world heritage sites and even at the Olympia music hall in Paris.

In the late 50’s, the revival of the Celtic harp happened, and Rock ‘n’ roll came along. When I first heard electric guitar – specifically music by The Shadows – I began to draw electric harps, dreaming of a Breton Rock music. No musicians were attempting to sing Celtic language to a rock beat or combine Celtic music with rock at the time. Later, the evolution of popular music helped inspire me: Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, the evolution of Irish and British popular music was taking the same direction to the one I had in mind.

In 1966, I started to sing along while playing my new metal strung harp, and everything progressed at a surreal speed. The same year, I had already performed abroad in Italy, and in 1967 I signed a contract with a major musical corporation. In June 1968, the Moody Blues (best known for “Nights of White Satin”), invited me to perform at the opening of their concert at the Queen Elisabeth Hall in London!

My first professional album – Reflets-Reflections – came out in 1970 and in it I tried to experiment with various “musical dishes”. It’s worth mentioning that, at the time, even an acoustic guitar was something new for Breton music, which usually only used bombards, bagpipes and acapella vocals. I kind of presented a menu to people by introducing a range of eclectic instrumentations: organ, Scottish bagpipe, cello, whistle, acoustic and electric guitar, etc. and of course, my Celtic harps.

By chance, my interests went together with the evolution of pop-rock and folk-rock music in the Irish and British Isles at that time. Groups that went in the same direction as me, and who interpreted traditional themes with a rock’n’roll groove such as: Horse-Lips, Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span. They very much helped me to reach audiences.

In 1971, my single ‘Pop-Plinn’, a kind of Breton-Celtic rock manifesto, reached a French radio programme. Then, after the Renaissance of The Celtic Harp, my career really took off after I played a concert at the Paris Olympia in February 1972. It was an incredible feat for a guy singing mainly in Breton (and a bit of English and Irish) to fill this temple of stars, after Edith Piaf and The Beatles! As millions of people listened to that concert, I can’t deny that this moment had an incredible impact. It actually changed the image of Breton music and culture outside of Brittany. The audience’s response was so huge that in only one-month, Breton music became International, and the inferiority complex evaporated. That was my aim.

Salomé: How did the public react to your music?

Alan Stivell: During the fifties, almost everybody was joking about Breton music. When I began to sing professionally, I was astonished by the way in which the public reacted to the music I shared. I never thought that what I made would have such success. I was delighted to see that people were moved by music that echoed and encompassed Breton sounds and the Celtic cultural world. My greatest wish is for a universal music to see the light, a universal music that would equally englobe various sounds and cultures. I wish I had a second life to further contribute to this dream!

Salomé: Do you find it easier to sing in some languages than in others?

Alan Stivell: Celtic languages are more fluid for my musical choices, despite French being my mother tongue. Of course, I also write naturally in French and try to do so in English as well. I have to say that the English-speaking music has influenced me more than French. I have been so emerged in French civilisation that I have always tried not to get rid of that side, but try to come to a « parity », imposing a real focus on the non-French part of my identity.

Salomé: As a singer-songwriter, what is your creative process?

Alan Stivell: Frome time to time, I am hit with spontaneous inspiration and few artists can say where these moments come from. On the other hand, I am also a bit cerebral and think a lot about what new field I would like to explore, what new road have I not yet been down. I don’t want to copy anybody, even myself. Often, there is a part of me saying : “you should try this out!” and I am happy to follow this voice, which helps guide me in my artistic decisions. Once I have come up with where I want to go, I let myself slip into inspirations. It’s important to embrace the unforeseen things too. I find an equilibrium between programming and improvisation, reason and emotion.

Salomé: As a Breton musician would you say that the sea is a muse? Are you pulled more towards the sea or the land?

Alan Stivell: The sea is all around the Celtic archipelago, from the Hebrides to Pornic (south of Brittany). The sea is central in our Atlantic-Celtic culture. I like to think of reality as being liquid – not in small boxes. I observe that all aspects of Celtic culture, philosophy and feeling share this same approach. The idea of borders, for example, is totally foreign to my universe. I like to embrace openness, interminglement, freedom and originality. In Breton language, the word Glas (pronounced ‘Glass’), means the eternal movement, the way of thinking. Glas has carved my soul and my music. Additionally, on a boat, I generally tend to the same musical modes, mainly defective hypophrygian. Of course also love the lands, the hills of our isles and peninsulas. Beyond that, I find beauty everywhere on Earth…

Salomé: What is the particularity of Breton music?

Alan Stivell: I always have been very enthusiastic about the music’s of my country. Freedom is the most important thing. I like evasions to dreamt lands having nothing to do with mine. For example, in my “Celtic symphony”, there is a part for church organs and strings which is influenced by composers such as Alban Berg and post-dodecaphonic sounds. I can go from a ‘séan nós’ piece to writing something Hip-hop sounding, electronic or metal-rock. I can dive into creative realms that are very distanced from Breton music. In the midst of my improvisations, I can play music that may recall flamenco, blues, jazz, Indian raga sounds… Above which I may sing in Breton, in English or in Quechua language.

The school of traditional Breton music and songs has been central in my education which was primarily classical. When I began, Breton, Irish, Scottish and Welsh traditional songs (and American with a Celtic background) were very important to my musical education. If Breton and Welsh music are more influenced by the continental European traditions (Wales is a special case with huge influence from classical music), there is a Celtic interpretation which is the most important to me. Special rubati, ryhmic and circular superpositions, other tempered and defective scales, crossing between phrases, asymmetry are things that I have studied, which give a meaning to the expression of Celtic music, an expression which is not considered serious by people who have not studied it. Most people stop just after the first listening or reading and ask: “are there reels and jigs in Brittany?” There is not a problem there. Breton music uses different basic materials in a Celtic way, and Gaelic music uses other materials and transforms elements in the same way, more or less.

Salomé: Why have you put so much emphasis on Breton culture in your artistic universe and beyond?

Alan Stivell: There were chapters of our history to be re-read. I wanted to put this culture into light and to incite people to rediscover it. We are now halfway there. We have delayed the extinction of Breton culture. In a metaphoric way, I would say that, for the moment, palliative care has been made towards Breton culture. I am sad though that the French government does not allow us to really save our language, still condemned to death if nobody helps us against certain policies and aspects of the constitution. Breton speakers are forbidden to get the Cornish official status, which I find outrageous!

Salomé: For you, what does it mean, to be an artist, and particularly a musician?

Alan Stivell: There is a duplication of personality (laughter). In my life, to be an artist has meant to do music and this does not just mean playing an instrument and singing. It also means to be human, to share emotions, to express a multitude of things. It means to explore one’s fragility, to put oneself into danger, to push oneself to one’s limits, and beyond.

Salomé: What is the role of music in your opinion?

Alan Stivell: Music enables to share all the aspects of life. I never decided to choose. I can psalmody a meditative piece translated into Tibetan or sing a drinking song as some do standing upon a table at a wedding. One can create and interpret simple and complex songs, and the songs that seem simple may actually be complex. “Son ar chistr” (My Cheers To You in my new version) for example, may seem simple, but the song’s structure is not. The same goes for “Tri Martolod”. Ultimately, music is infinity.

We thank Alan Stivell for his time and generosity, and Salomé for having taken the initiative of conducting this interview and translating it from French into English.