E&M author Tess Lowery takes a look at anti-rape campaigns across Europe and wonders what can be done to make them more effective.

Content warning: contains a discussion of sexual assault and rape

“No means no”? You’ve got to be kidding me. How about “yes means yes”? Thanks to a number of legislative changes over the past year, the latter appears to have eclipsed the former, as more people are told that they must have explicit permission from the object of their desire before they engage in any sexual activity.

Several universities in the UK now offer their students sexual consent classes although there is still no such thing in any other European countries. A small group of students have felt offended by mandatory sexual consent classes and disagreed with the implicit message that they do not know what consent is. Many more students have dismissed these initiatives as a waste of time since the kind of person that rapes is presumably not the kind of person that turns up to these classes voluntarily. These people sadly believe the myth that rapists are morally corrupt monsters lacking any shred of empathy. In fact, the reality is that they are more often people we know, even people we trust. So the question is, does actively forcing consent classes on young people weaken the overall attempt to open up a discussion about consent?

Sex-ed

Personally, I do agree that sexual consent classes should be mandatory for secondary school students. I also think sexual consent classes might even be a good idea for university students. Rape, sexual harassment and assault still affect a worryingly significant number of female students across the continent. When asked what rape is, most people will give you an immediate answer. But if you described a non-consensual encounter, many of these same people would not call it rape – because the term “rape” itself is a very loaded one.

I went to a rape awareness event recently where the audience was asked to close their eyes and imagine a rape. We were asked to imagine where it happened, to think of an object close by and what the victim did the next day. Almost everyone imagined the place to be an alleyway, the object a dumpster or a knife and the actions of the next day usually involved going to the police. Real rape victims undertook the same experiment and the reality was that the place was usually a bed, often the matrimonial one, objects included a teddy-bear and a wedding ring and the next day, the victims usually just got on with their lives. There is clearly a disconnect between rape and non-consensual encounters in most people’s minds where there shouldn’t be.

Luckily, sexual consent classes are not predominantly about informing you about what rape and sexual assault are. They’re about grey areas that we cannot really define. Flirtation by its very nature depends on the implied, not the overt, so it’s easy to see that some people might think that consent can also be implied. Some other ambiguous spaces include the line between “reluctant acquiescence” and “coercion”. If your boyfriend asks for a quickie and you’re tired but you agree, “okay fine”, this would not constitute rape. In cases of the sexual grooming of very young girls, however, victims often do not realise that the intimidation and pressure they encounter means they have not freely consented to sex. Many people also do not know that someone who is very drunk cannot grant their consent.

Say sexual consent classes were enforced in all European countries tomorrow, the question remains: what do we do with the generation just that little bit too old, the one that missed out on this precious sphere of education? That’s my generation. The one that got one video about childbirth and maybe a demonstration of how to put a condom on a banana. The idea that sex might be for pleasure was completely alien to us.

Here’s the problem with consent classes: they aren’t sexy. Yet, sex sells. We all know it. Sex pervades almost every part of the advertising world. Further, when you buy sex in advertising, you get certain values and attitudes as freebies – a kind of sick “buy one case of sex appeal, get a box of misogyny free!”. Quite often these attitudes are derogatory ones towards women. Next time you see a high-end perfume advert exhibiting a scantily dressed woman sprawled across a divan looking passively towards the camera, a man hanging ominously over her, ask yourself what this body language implies. We 21st century kids think we’re immune to advertising, but we’re not. Just as we think we’ve become wise to advertising’s tricks, advertising itself has evolved, too. Clearly, advertising is partly responsible for rape culture. Because of this, it needs to help set right this wrong. For consent classes to grow in popularity, they need a much sexier ad campaign.

The do’s and don’ts of selling consent

For many dark years now, the trend has been for anti-rape adverts to warn victims of the dangers of walking home at night; the dangers of going home with strangers; the dangers of drinking – the dangers of existing. Catch-lines abound, such as, “Which of your mates is most vulnerable on a night out?”, “When you drink too much you lose control and put yourself at risk” and “Some decisions leave friends vulnerable to date rape”. A Hungarian official public safety video shows three girls getting dressed up for a night of Tequila shots and dancing. Not only does it dwell excessively on the sexualisation of the women as they get ready to go out, the catchline is “You are responsible, you can do something about it.” In Italy, the national Telefono Donna rape helpline launched a campaign that featured naked women in crucifixion poses on beds that themselves screamed of sex appeal. No, you cannot make an anti-rape advert that is literally sexy.

The issue here is that the blame victims for making bad decisions and letting themselves be raped. It’s also easy enough to imagine that rape prevention adverts aimed at potential rapists would never work because they are drooling psychopaths beyond the reach of the advertising world’s grasp, right? Wrong.

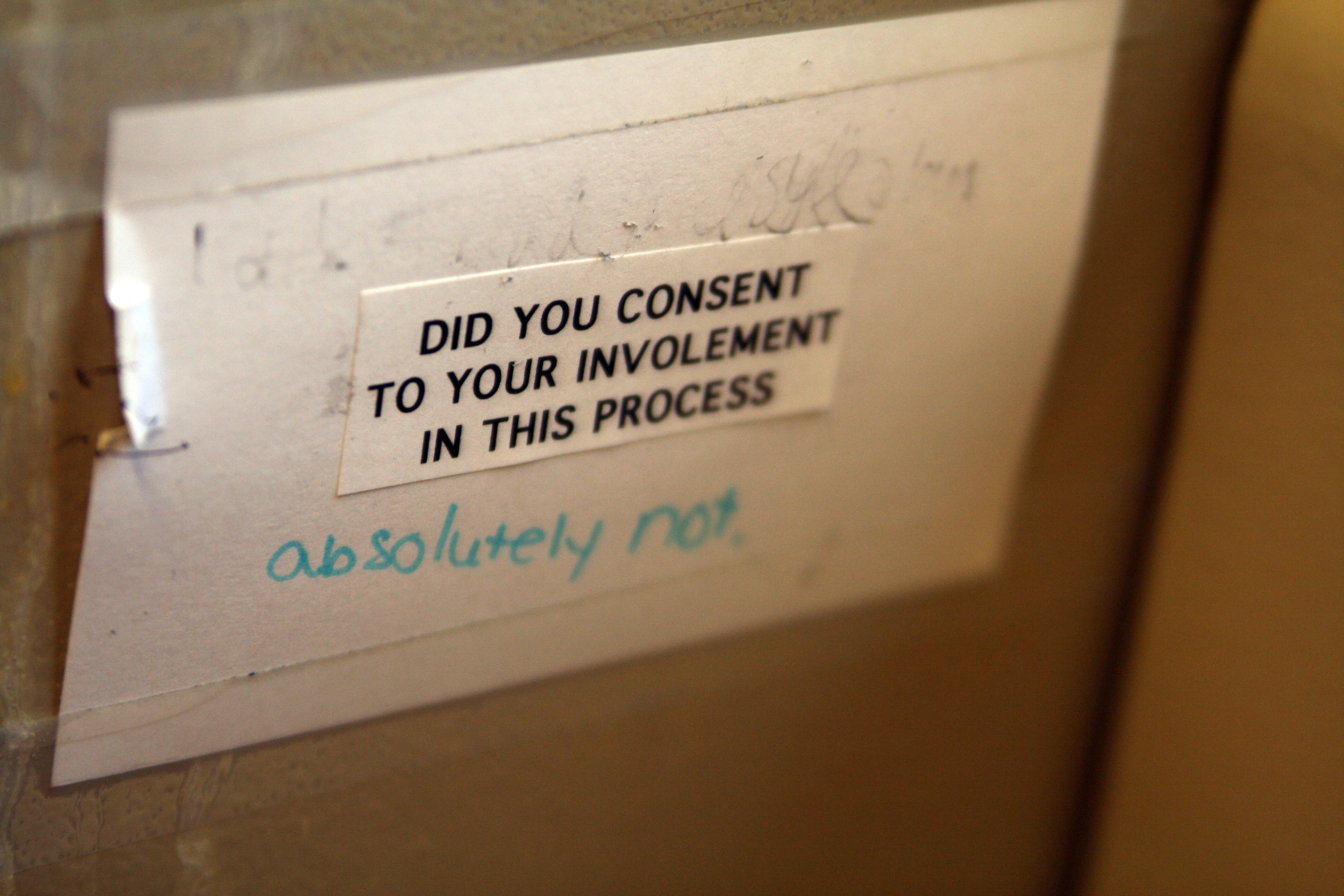

A few avant-garde advertisers have seen the light. One campaign had the particularly harrowing slogan, “If you could see yourself would you see rape?” One of its adverts featured two teenagers kissing in a bedroom at a house party. When the girl suggests she wants to get back to the party, the boy grabs her and pushes her onto the bed. A second version of the teenage boy is seen banging frantically on a glass wall separating him and the couple shouting: “Stop! She doesn’t want to. What are you doing? Just stop!” It was brilliant because it showed just how close to home rape actually is, in a way that prior adverts hadn’t even attempted to. These adverts were visceral, hard-hitting and effective. Then came the “Don’t be that guy” campaign aimed at men between the ages of 18 and 25. The most eye-catching of their posters depicts a young woman in red tights and a short black dress lying face down on a sofa with several empty bottles of wine strewn across the floor. The tagline read, “Just because she isn’t saying no doesn’t mean she’s saying yes”. This campaign was a success and sexual assault actually dropped by about 10% in the area they were trialled.

More recently, an ingenious campaign that equated sexual consent to drinking cups of tea hit the Internet. Viewers are asked to imagine that, instead of initiating sex, you ask someone if they’d like a cup of tea. They say they’d love one. Then you know they want a cup of tea. You make it for them, they drink it. If you ask them if they want tea and they say yes please and then when the tea arrives they say they no longer want the tea, don’t make them drink it. They are under no obligation to drink the tea you’ve made. Some people change their mind in the time it takes to boil the kettle. If they’re unconscious, don’t make them tea. Unconscious people can’t drink tea and they certainly don’t want tea. They can’t answer the question “Do you want tea?” because they’re unconscious. It all seems very obvious, which is both entertaining and potentially problematic. If sexual consent is equivalent to tea-drinking consent then why is the former systematically misunderstood by so many people? However, despite its flaws, the ad in question is designed to make people think about sexual consent in the same terms they would any other consent and for this it should be commended. If you wouldn’t make someone drink tea, don’t make them have sex.

So, what do all of these campaigns have in common? They are rape prevention campaigns aimed at potential rapists. It’s about time the blame shifted from the victim’s and onto the sexual aggressor’s shoulders. Not only is this simply the right thing to do, the evidence shows it works, too.

Featured photo: Quinn Dombrowski (Flickr); Licence: CC BY-SA 2.0