The EU agreed to resume accession negotiations with Turkey in November 2013, having seen the process stall for the past three years. E&M looks back at Turkey’s long-term relationship with the EU and asks whether this latest step really pushes the ongoing affair into something more permanent.

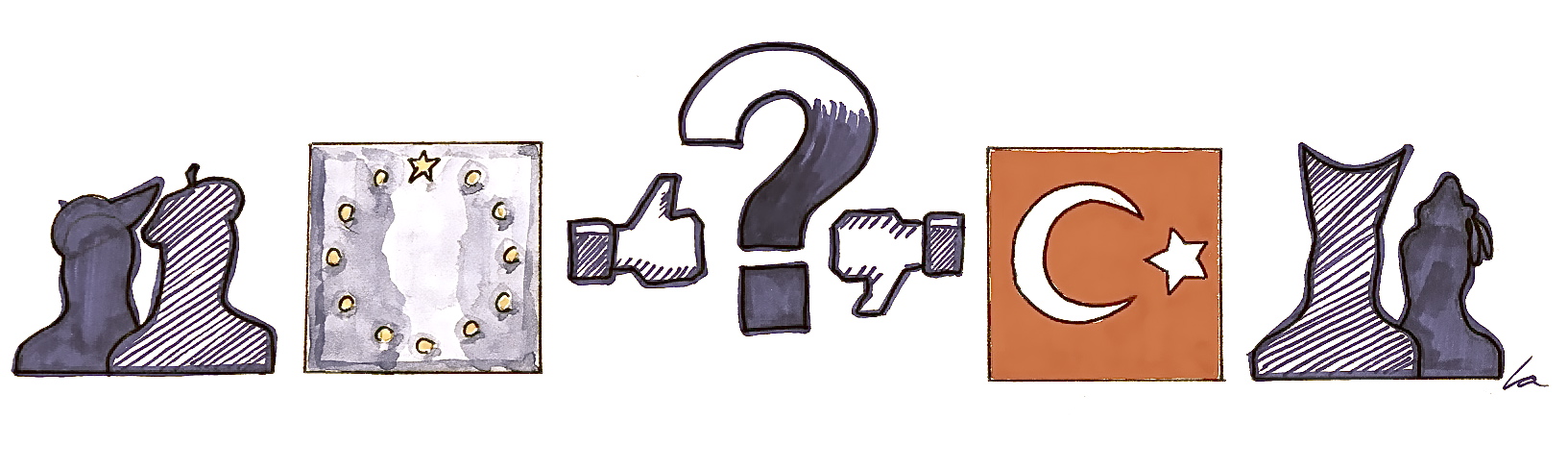

It’s complicated!

If Turkey and the EU had facebook accounts, their relationship would read “it’s complicated!” The latest statements on Turkey’s renewed accession negotiations with the EU are nothing more than the next step in a protracted love affair. Both sides need to take steps to turn this long-term partnership into something more, a marriage, if marriage is in fact the the ultimate aim for both.

The EU is now at a point where, despite recent progress, it risks losing Turkey as a successful candidate country and instead is fuelling euroscepticism on both a popular and elite level. A civil servant, an officer working on EU affairs for the Turkish Government, who agreed to comment anonymously told us that ‘the blockages in Turkey’s accession process could be disappointing, sometimes undermining the EU’s credibility.’

There remains optimism on the Turkish side that despite setbacks, there can still be progress towards full accession though. As the EU officer argued, ‘When both parties become ready, I believe Turkey will be a full member of the EU.’ As the last 54 years have shown however, both countries have taken their time getting to know each other and may yet be just as far from accepting full membership as they have been.

Turkey’s long road to accession

A brief history of Turkey’s relationship with Europe should begin in 1959 when Turkey applied for the associated membership in the European Economic Community (EEC). The parties then signed the Ankara Agreement in 1963, which aimed at bringing Turkey into a customs union, leading to full membership application in 1987. Negotiations were legally opened in 2005 meaning that Turkey was given ‘The conditions and timing of the candidate’s adoption, implementation and enforcement of all current EU rules.’ These are divided into what are called The EU’s 35 policy chapters, to be ‘closed’ or signed, before accession.

Only negotiations on Chapter 25 (science and research) have been opened and provisionally closed.

As of November 2013, only negotiations on Chapter 25 (science and research) have been opened and provisionally closed. 13 Chapters are now open, but not yet provisionally closed and in 2006 the European Council decided to freeze 8 Chapters. These chapters relate to Turkey’s failure to apply the Additional Protocol of the Ankara Agreement to Cyprus, as Turkey does not recognise the Republic of Cyprus (an EU country).This was most clear during the EU presidency of Cyprus in 2012, when Turkey boycotted its ties to the EU Presidency under Cyprus.

Yet this quite obvious issue, is not the only stumbling 4 block to Turkey’s accession. For a period of more than three years starting in mid-2010, the relations between Turkey and the EU entered a period of stagnation. Nobel-prize winner Orhan Pamuk has argued that the whole project of joining the EU fell apart in this period. Since then, ways were sought to keep the relations moving at least a little to 5 stop the process groaning to a premature halt.

For the EU, Turkey was slow in her reforms and human rights issues raised concerns, problems that are still ongoing. For Turkey, the EU has demonstrated a reluctance and insincerity to the eventual goal of securing Turkey as an EU member divided into what are called The EU’s 35 policy chapters, to be ‘closed’ or signed, 2. Since then, ways were sought to keep the relations moving at least a little to 5causing a rising euroscepticism. According to Eurobarometer surveys, support by the citizens of Turkey for EU membership decreased from 71% in 2004 to 36% in 2012.

Positive Agenda

The current solution to the malaise that has struck the EU/Turkish relationship was initially launched in 2012 and named as a ‘positive agenda’. It does not aim to replace the ongoing negotiations but rather energise progress on the treaty chapters. The civil servant we talked to suggested that this was a positive step and “There is no doubt that positive agenda has brought a new dynamism to EU-Turkey relations.”

The Agenda “has allowed Turkey to continue her alignment efforts with a new impetus” they added. Common interests on issues such as the alignment with the EU legislation, visa liberation, mobility and migration, trade, energy, counter-terrorism and foreign policy are all areas of cooperation encouraged under this agenda.

Turkey and the EU now cooperate in active working groups to revive the accession process, collaborating first on judicial and Fundamental Rights issues. The tangible results from these steps are clear, and after three years the afrench have signaled the removal of their block on chapter 12 of the negotiations and progress can be made once more on the path to integration.

Turkey’s Progress Report 2013

The publication of the EU’s latest progress report for Turkey, in October 2013, reveals a mixed picture of where Turkey lies on the path to accession and despite the resumption of talks gives an indication of how far Turkey still has to go. These reports, drafted by the European Commission, set out an evaluation of candidate countries’ ability to take on the obligations set for gaining their EU membership.

The protests in Gezi park were taken as a sign of a growing civil society within Turkey.

In the most recent report, the use of excessive force against demonstrators during May-June protests of Gezi park was criticised. The protests were taken as a sign of a growing civil society within Turkey, a positive step, but with the caveat that it was clear that civil society was still not traditionally considered as an inherent part of Turkish democracy. This was clear but the framing of the protests by the Turkish Minister of EU Affairs and the Chief Negotiator Egemen Bağış that these protests were “violence and illegal methods [which] can never be seen as a means to claim one’s rights” demonstrates how poorly they were considered among many of the Turkish political elite.

The democratisation package and peace process on Kurdish issue are also significant for convincing the EU that the reform agenda is making progress. Turkey still needs to develop a way of relying on democratic processes rather than shifting to polarisation and relying on the parliamentary majority of the ruling party.

Human rights issues and the establishment of the rule of law remain areas of concern. Discussing these chapters, the Turkish EU officer asserted that “These criticisms would be taken seriously by Turkey and would guide the new reforms in Turkey.” As expressed by Egemen Bağış, the 2013 Report was being taken as ‘an official record of Turkey’s determination for reforms’ rather than a record of success or failure.

Turkey and the EU now cooperate in active working groups to revive the accession process.

With this in mind, it is hard to conclude whether the recent developments in Turkey-EU affairs are promising or not. But at least something is happening and progress is being made. As Štefan Füle, Commissioner for Enlargement and the European Neighbourhood Policy, pointed out in 2012 “When I ask my Turkish partners where they see Turkey in five, ten or twenty years from now, they all say ‘anchored in Europe. When I put the same question to my interlocutors and politicians in the EU, the answer is the same: they see Turkey’s future as a modern European state.”

If Štefan Füle is correct, it is promising to find that both parties have a common understanding of the future end-state for Turkey and the EU, and movement to accession can genuinely be considered to be progress. That is not to say that we can predict if and when accession will take place, whether it’s five or in twenty years’ time. I am not that optimistic and my question remains: Will I, as a 25-year-old man, be able to see the actual marriage, before I retire?

Cover photo: Laura Hempel