In ancient times, people told myths. Today, we watch reality TV. But are the two as distant as it would appear at first glance?

Switching on the television, there is a good chance of finding yourself three hours later trapped in front of the flickering and pearly-white smiling face of a young presenter showing (more than telling) you the story of an “average” person, fleeing his or her “average” life, and you know: something great is going to happen to this poor guy – what could be worse than being average? Usually, we call this genre of entertainment “reality TV”; or, in society’s drunkenly honest moments, trying to signal the truth elegantly while barfing it in your face: “scripted reality TV”. While it is easy to judge and ridicule this (post)modern form of entertainment in its often ideologically loaded, denigrating, chauvinistic and emotionalising form, something about these shows tickles people at a sensitive spot.

They seem to help us overcome the easy feeling of disconnectedness from the world that accompanies our brain’s flickering in perfect harmony with the colourful pictures in front of us: a story is being told, a myth created, the world is transformed and sometimes a hero is born. Despite its new form of consumption and production, entertainment that satisfies this human desire for stories is not a new phenomenon. It seems to be neither dependent on a flickering black box nor a pearly-white smile: a wooden chair and grandma’s toothless mouth had the same effect in pre-modern Europe.

In a certain way, our imagined Saturday-night couch adventure has its parallels in earlier times. In pre-modern Europe people would listen to stories passed on from one generation to the next, passed on through times and at some point written down – saved for (or maybe from) history. They may not have sat on a couch eating crisps, and the story was not interrupted by advertisements for “the super sickle” or the “tough guy’s plough”, but the legends grandmothers told their grandchildren centuries ago share certain characteristics with our modern forms of entertainment.

They may not have sat on a couch eating crisps, but the legends grandmothers told their grandchildren centuries ago share certain characteristics with our modern forms of entertainment.

Consider for example the so-called “Nibelungen Saga”, a story that was told during the middle-ages by people in the northern regions of Europe. In this saga, we learn about the fate of Siegfried, the prince of a Kingdom named Xanten. After his parents are slaughtered in a bloody battle, he survives and is raised by a stranger under a different name – only to later find out that he, the poor but proud blacksmith, is a powerful king. Is it not exactly this transformation from average to great that aroused so much excitement over Paul Potts, a not especially handsome mobile-phone seller, who became famous within weeks all over the UK and big parts of Europe because of his beautiful opera voice (and the promotion of “Britain’s got talent”)?

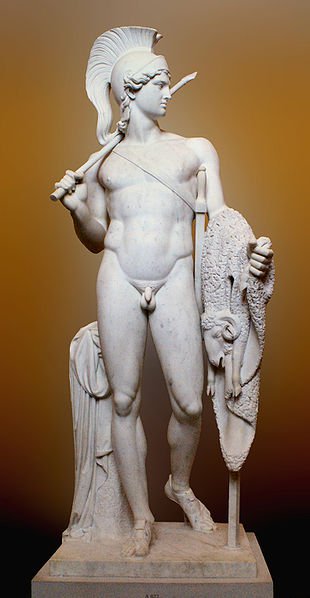

A similar parallel can be drawn between ancient myths and modern reality TV shows in other European countries. Jason’s journey to capture the Golden Fleece is fraught with difficulties and obstacles – among them is a terrifying storm, an army of undead soldiers and an island full of women who are seducing Jason and his team (the Argonauts) only to sacrifice them eventually. The modern equivalent of this story is to be found in shows such as “goodbye Deutschland” – a series where people (often an entire family) leave Germany to find a new life somewhere far away. It might appear that this comparison is unfair since Jason had no idea of what kind of adventures were waiting for him, whereas today’s German emigrants probably planned their journey and know the country and region they are moving to – those who have seen the show, however, know that this is not true. Often the participants have no idea what they are in for. Still, while pointing to an important parallel between today’s and pre-modern forms of entertainment, the examples described here also point to important differences.

Clearly pre-modern heroes had to face and overcome obstacles of a different quality than their modern counter-parts. While Paul Potts only had to sing a song on a frighteningly big stage with the reward of bathing in applause afterwards, beautifully golden-haired Siegfried had to kill a frighteningly big dragon with the reward of bathing in the dragon’s blood afterwards. The attentive observer might see a qualitative difference between these adventures that makes them more or less incomparable. Along the same lines: Jason faced many difficulties of which he could not be aware when departing for the Golden Fleece. For heroes in Greek antiquity, journeys were quite difficult to plan: you always had to take into account “the unknown” (not everything was explored), but far more important: the ever unstable will of the gods who tended to interfere with the lives of the great. For our modern TV emigrants, the unknown is often the product of insufficient planning; the ones who might interfere in their live-plans are not the gods but sometimes the visa issuing authorities in the countries of immigration and their ever unstable will.

These differences lead some nostalgics to dream of the good old days, where entertainment was still about the brave, those who were willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater and common good (and knew what this was). These heroes saved children, women, entire cities; they found treasures, sailed the sea, slayed dragons and bathed in their blood; killed enemies – all for the good of society.

Think about Big Brother, a show where people are locked inside a house so that the observer behind the TV-screen can watch them have awkward but heroic sex under the sheets.

Shouldn’t we go back to such educational forms of entertainment, where fighting for good is rewarded? At least to me, this kind of thinking, of one man or woman saving the world from the “bad”, of one great idea about human togetherness seems rather scary than something I would embrace. Haven’t we seen the emergence of such ideas and their terrifying consequences in the more recent chapters of history?

Proponents of pre-modern heroism would sometimes go further, pointing out that while ancient heroes killed for the greater good, today’s entertainment comes down to only two things: sex (ual attraction), which serves as an instrument to increase consumption. Even though we may not follow this argument easily in the case of “goodbye Deutschland” or Paul Potts, in other cases of (scripted) reality TV, this tendency is clearly identifiable: think about Big Brother, a show where people are locked inside a house so that the observer behind the TV-screen can watch them have awkward but heroic sex under the sheets; think about other casting shows in which new stars are born – models, singers, you name it. Don’t they, above all, need sex-appeal? Shouldn’t we want to go back to our pre-modern heroes with their beautiful long hair and their search for “the good” instead of promoting dirty sex?

In a certain way, these nostalgics miss the point. As the fantasy writer Goerge R. R. Martin explains pointedly: “When I describe how an axe enters a human skull in great detail, no one will say a word; but when I describe how a penis enters a vagina with the same level of detail, I receive letters of complaint. […] Penises entering vaginas have in the course of history led to a lot of joy. Axes entering human skulls have not done any good, whatsoever.”

Still, there may be a point to some of this critique and what we are seeing on reality TV is in fact not new heroes, but rather new fools – a type of characters that also often appears in pre-modern stories. Maybe the species of publicly appraised heroes has died out and today’s heroes act rather in the private and resemble Lermontov’s anti-hero: “I’ll hazard my life, even my honour, twenty times, but I will not sell my freedom. Why do I value it so much? What am I preparing myself for? What do I expect from the future? In fact, nothing at all.” If this is true, looking at the history of entertainment leads to an interesting realisation: types of heroes change, stories, however, are always told. Be this the myth of entertainment, entertaining a myth or an entertaining myth – let’s just hope I fit the next category of heroes.

Cover image source: Wikipedia