“The Knight in the Tiger’s Skin” – a powerful Georgian epic of adventure, love and philosophy. Created by the mysterious Shotha Rustaveli, the gallant hero Tariel has more than earned his place at Arthur’s Round Table.

In this column, we explore the wonders of Europe – artistic masterpieces and jewels of cultural heritage. These are the treasures which fill us with a sense of Europe’s complex past – how beliefs and identities have intertwined to create the continent and the nations whose borders are often so hard to define. In the third instalment, Ziemowit Jozwik takes us to the Caucasus in search of Tariel, the Knight in the Tiger’s Skin.

A knight there was, and that was a worthy man,

Who from the time that he first began

To ride out, he loved chivalry,

Fidelity and honour, generosity and courtesy.

G. Chaucer “The Knight’s tale”

In fact, the knights were there. If we sit back for a moment and try to imagine the medieval beginnings of Europe, first of all we will be dazzled by the autumnal sunbeams glittering on the plates of a knight’s shining armour. Errant or not, knights wearing heavy, uncomfortable armour as a reminder of rigid knightly virtues, wielding their intricately decorated swords and confiding in their loyal horses constitute the imagined scenery of Europe in its infancy. In poems, epics and occasionally also in reality, they followed all the rigorous demands of the chivalric code which forms the basis of European moral identity.

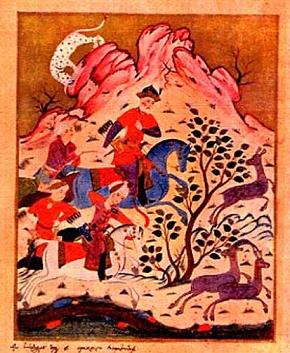

Almost every European country has its “knight in shining armour”. El Cid Campeador, Charlemagne’s Roland, the English Sir Gawains and Sir Lancelots of the Round Table or the Polish Zawisza the Black who never told a lie – these are only the most well-known examples, among whom “Vepkhistqaosani” may sound unfamiliar at first. But in fact this Vepkhistqaosani, the Georgian “knight in the tiger’s skin” is a full member of that European community of brave knights.

The purling sound of the tongue-twisting and palate-itching word Vepkhistqaosani gives us a shivery impression of a fog-wrapped, far away country hidden in the Caucasian valleys – Georgia. Its foreign sound lets us see that remote land faintly in the distance – perhaps just as dimly as Jason and the Argonauts saw it, when they set out for Georgia on their quest for the Golden Fleece. But that faltering impression of Prometheus’ motherland might become clearer with the help of that unpronouncable word.

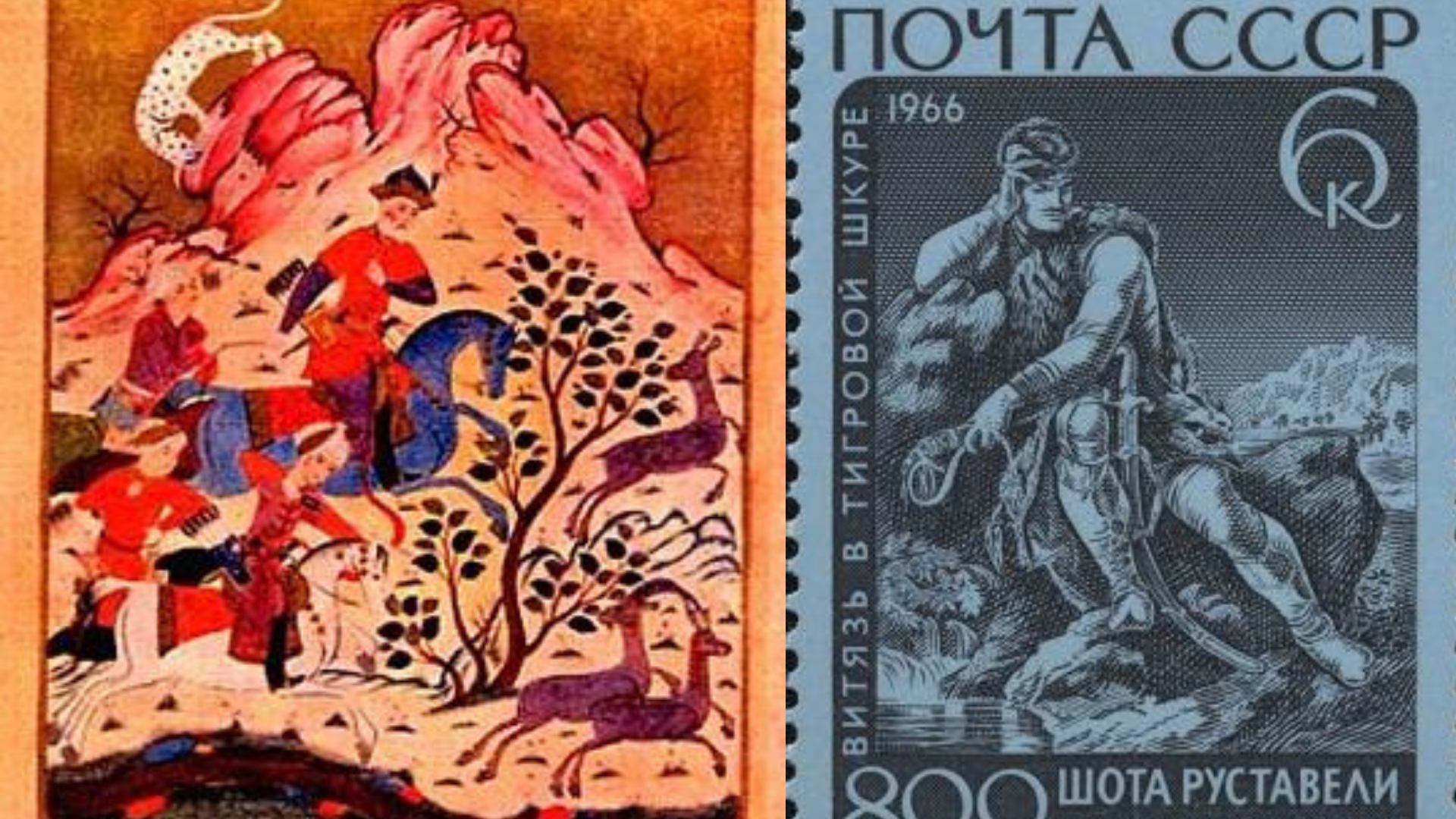

Vepkhistqaosani, “The Knight in the Tiger’s Skin,” is the title of the Georgian national epic and one of the greatest fruits of what is called the Georgian renaissance. It is almost a complete symbol of Georgian culture in its golden age. Written in the 12th century by the multi-talented Shotha Rustaveli, the poem reflects the Christian cultural environment in which the country had flourished since 337 as well as a deep understanding of Islam, the religion of Georgia’s neighbours. Besides some references to Arab and Persian tales, the poem shows typical features of medieval attitudes. However, in many ways it is also a forerunner of the traditional ideals of the European renaissance, which were to be “invented” in Italy about two hundred years later.

Unluckily, philosophy was not Shotha Rustaveli’s only fascination.

But let’s start at the beginning. Of course the poem opens with a carefully crafted invocation of God. However it is not the typical “ad maiorem Dei gloriam” (For the greater glory of God) formula but a passionate appeal to the “mighty power” who “created the firmament” and “the world infinite in variety” and can “give mastery to trample on Satan” or “the longing of lovers lasting even unto death”. The image of the “one God” reveals some mystical, Sufi Muslim influence but also resembles Michelangelo’s Heavenly Father from the Sistine chapel. This is an effect of Shotha Rustaveli’s studies. The poet studied in the Greek city of “Aegen” – perhaps Athens or Mount Athos; he was taught the liberal arts and was especially fascinated by Greek philosophy. That specific construction of “God made only what is good”, comes from Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite who was one of the most influential theologians at the turn of antiquity and the Middle Ages and reconciled Greek thinkers and Christians.

Unluckily, philosophy was not Shotha Rustaveli’s only fascination. He fell in love with T’hamara, the “jet-haired sun-queen.”

“Her eyebrows and lashes, her hair, her lips and teeth, cut crystal and ruby arrayed in ranks. An anvil of soft lead breaks even hard stone”

Queen T’hamara, whom “by shedding tears of blood we praise,” was the ruler of Georgia and the inspiration of Rustaveli’s writing. As a major supporter of the Georgian renaissance, T’hamara was not a type of ruler who toed the line, but one of the greatest in the whole Georgian history. That is why she inspired poets. For example she was virtuously eulogised by Rustaveli’s friend Chakhrukhadze as “the ruby-cheeked, the jet-haired sun-queen”. That may explain Rustaveli’s fit of passion. As a queen’s treasurer and one of the most important statesman who knew Roman law and all the convoluted twists and turns of Caucasian geopolitics like the back of his hand, he fell in love with T’hamara. Even though some unromantic academics consider that love to be no more than a folk fairytale story, which as a legend bequeathed by word of mouth endured together with the poem, we still can’t escape the impression that that unrequited love affected the whole structure of “The Knight in the Tiger’s Skin”. The martyred lots of lovesick heroes cursed with “pitiful fainting and dying,” asking “what love dost thou think this?” became a parallel of Rustaveli’s tragic affection. The poem became a passionate expression of his tortures. According to tradition, it was this that led him to move to the Monastery of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem where he assumed a monk’s habit and painted a series of frescoes. And actually these frescoes are the only tangible evidence of that Georgian Homer’s life.

“In the Arabic tongue they call the lover ‘madman’…”

But even before he became a painter, Rustaveli possessed a painter’s great sensitivity for colours and details. His descriptions draw us into the landscapes of fictionalised countries, making us feel like participants. His characters are not artificial figures – the beautiful “donna angelicata” (angelic lady) or the fearless “chevalier inflexible” (unbending knight). Rustaveli’s characters are constructed with psychological insight showing the contradictory feelings and temptations which tug them in different directions, and the moral rules which restrict them. For example, the tiger-clad knight Tariel was a loyal and beloved servant of his monarch until he fell in love with the king’s daughter. Here we can observe an outstandingly dramatic fight between Tariel’s sense of honour and loyalty to the ruler and his frantic passion for his daughter.

“Sages cannot comprehend that one Love; the tongue will tire, the ears of the listeners will become wearied; I must tell of lower frenzies, which befall human beings;

In the Arabic tongue they call the lover ‘madman,’ because by non-fruition he loses his wits.”

In contrast to the “madmen”, women are more stable. Rustaveli approaches them with more respect, gently lifting the veil of mystery from woman’s interior life. Throughout the epic, this specific approach to women reveals their significance in Georgian society, symbolised by the queen T’hamara. Women are not only objects of loving sighs but are members of the Georgian society and may become the “blood-brothers” of knights, as one of the main heroines did.

Another reflection of Georgian morality is the noble, philanthropic and generous friendship which the knights Tariel, Avthandil and Phridon show each other. The typical, highly valued demands of the knightly community such as respect, munificence or disinterested, voluntary help and mercy are expressed by the words of Plato, quoted by one of the heroes.

“A wise man cannot abandon his beloved friend. I venture to remind thee of the teaching of a certain discourse made by Plato: ‘Falsehood, and two-facedness injure the body and then the soul.’

Since lying is the source of all misfortunes, why should I abandon my friend, a brother by a stronger tie than born brotherhood? I will not do it!”

A knight quoting Plato, interesting. As the Georgian renaissance began, due to an influx of humanist ideals and the support of T’hamara, something like a “Neo-Platonic” school blossomed in the country. Rustaveli was an enthusiastic propagator of this school; his work expresses the ideas of thinkers such as Ioane Petritzi, who was one of the greatest and most influential of Georgian philosophers and a translator of ancient Greek philosophical treatises.

The fascination of ancient philosophy during the Georgian renaissance is shown in the subtle anthropocentrism of “The Knight in the Tiger’s Skin”. Characters appreciate the value of earthly life, enjoy the beauty of the material world and sometimes even play tricks on each other – which the author does not condemn, preferring to turn a blind eye to some people’s weaknesses, especially when love is at stake.

“Some have nearness to God, but they weary in the flight; then again, to others it is natural to pursue beauty.”

Tariel, Avtahandil and Phridon share these anthropocentric ideals with their creator. Apart from being unblemished knights in shining armour who appear to have galloped straight into the poem from Arthur’s Round Table, they “show mercy to the vanquished” as this is good in the eyes of God and an indispensable rule to “cling to if you want to live decently and would like to die easy”.

This article could only give a short impression of how “Rustaveli praised Tariel, for whom his tear unceasing flows”. All across Europe, from Arthur’s Cornwall to Tariel’s Caucasus, the knights were there – and perhaps they are still somewhere, errantly wandering about the borders of our moral reflections, from time to time assisting our choices, with their visors raised, tilting at the windmills of our faint-hearted weakness.

And among those knights is Vepkhistqaosani, the knight in the tiger’s skin, from the not so distant Sakartvelo, as the Georgians call their homeland.