In September 2015, much to the surprise of political commentators across the United Kingdom, Jeremy Corbyn won the Labour party leadership race. A relatively unknown individual on the national stage, this backbench Labour MP known in political circles for his commitment to the far Left and its causes, claimed 59.9% in the first round of voting thereby winning a landslide victory over the other candidates. This surprised many due to prevailing centrist and pro market trends in British politics, deeming someone of Corbyn’s views practically unelectable. Nevertheless, not only did he attain a higher percentage of the vote in every age group (from 18-65+) than his fellow candidates, his election as Labour leader corresponded with a growth in party membership from 201,293 to 388,407 by January 2016. Evidently, his socialist message has strong appeal, a political trend echoed broadly across Europe and visible in radical socialist parties such as Podemos and Syriza, rising to prominence in Spain and Greece respectively. Such new Left initiatives across Europe share some common objectives, most notably opposition to austerity policies that place the burden of economic crisis on the most vulnerable, aversion to foreign intervention and an admittedly vague but heartfelt plea for a ‘different type of politics.’

A welcome breath of fresh air

Anti-austerity protests in Spain

With hindsight, it is easy to see how British politics after the 2015 election had space for a Corbyn-like figure. In many sections of society, particularly the lower ends, there was a tangible sense of disillusionment aimed at the political class. The argument for post crash austerity put forward by Conservative chancellor George Osborne and imbibed by much of the media went unchallenged by Ed Miliband, –leader of Labour in the 2015 general election – as well as candidates competing with Corbyn in the Labour leadership election. They came across as yet more tedious career politicians devoid of passion, concerned solely with rising through the ranks of the party and adhering to a media standard of respectable electability, rather than actually affecting meaningful change. A continuing confidence in austerity disproportionately affects some of society’s most vulnerable, including disabled people unable to work, the working class and the young. Indeed, in keeping with such policy the income inequality gap is increasing in the United Kingdom, with the top 10% receiving a net income of £79,042 (101,505 €), almost ten times that of the bottom 10%, and the top 1% receiving an average income of £941,582 (1,209,730 €). As such, Britain is one of the most unequal developed countries in the world, third in Europe behind Spain and Greece.

Evidently, the British political system was calling out for a ‘breath of fresh air,’ a phrase consistently applied to Mr Corbyn. Even his appearance contradicted the existing political class; the natural, unpolished gestures during public events, a genuine and spontaneous manner in interviews; even his casual choice of clothing gave the impression of a “real person”, in stark contrast to monotonous peers, breezing through prepared speeches; moving from buzzword to buzzword. The value of his authenticity cannot be underestimated at a time when politicians are seen by many to be untrustworthy and primarily concerned with image. His underdog image was furthered by the fact that the rest of the political elite – rival parties, the press, old Prime ministers and even his own party – were and still are desperate to stop him. This likability factor was partly responsible in galvanising young people with a natural affinity towards politics of hope to embark on a mass social media campaign.

A real socialist in the traditional sense

Certainly though, he is not simply refreshing in terms of image. His straightforward message and espousal of concrete socialist ideals saw him emerge as a true Labour candidate in the traditional sense; a genuinely oppositional figure to the Tories. He put forward unapologetic arguments against austerity, exhilarating young voters like myself who were hearing the socialist case being made with passion and directness for the first time. By focusing on issues that disillusioned voters have seen dismissed and often aggravated by current policy, he shifted the boundaries of the political debate in a positive way. One example is his desire to abolish tuition fees, a real issue of contention over recent years. The threat of student debt has never been as heavy as it is now. Personally, I feel that leaving university with over £50,000 in debt (63,636 €) lends itself to serious financial insecurity, and with plans to privatize existing debt and raise tuition fees in the future, young people of lower socioeconomic strata’s are much less likely to go to university. If such policy trends continue we will see the inequality gap rise even further as the best education becomes reserved for the richest.

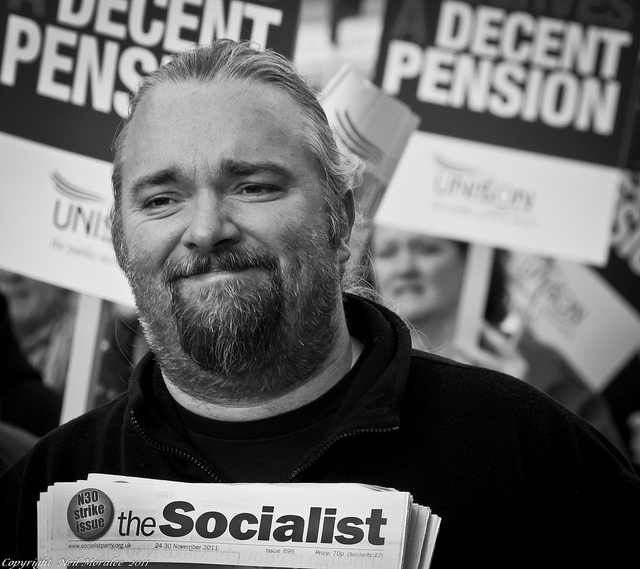

Corbyn’s espousal of concrete socialist ideals exhilarates young voters hearing the socialist case being made with passion and directness for the first time.

Another meaningful issue he addressed is that of private rented housing, especially severe in London, where many tenants have no security of tenure, extremy high rent and energy costs and profit driven landlords, pushing those most vulnerable aside. This trend is reflected across Europe; according to research conducted by Habitat for Humanity, more than 10% of Europeans bear housing costs exceeding half of their household income; and in central and eastern Europe, households spend between 30 and 50% of their income solely on winter heating. The austerity-inspired policy of capping housing benefit is exacerbating the problem in London and effectively forcing people away from their homes, as is the case for about 133,000 families. A letter to the editor of the Telegraph aptly describes what Corbyn achieved by directly addressing such issues: he has emerged as “the only contender for the Labour leadership who clearly espouses the socialist ethos of workers’ rights and public ownership, the twin pillars of Labour principle.” Indeed, it was not only the youth that Corbyn appealed to, working class people were fittingly represented in his supporters, with only 26% of them possessing a household income of more than £40,000 (50,913 €).

Our cultural understanding of socialism, particularly for the millenial generation, is no longer marred by the failures of the USSR.

That Jeremy Corbyn openly identifies his philosophy as ‘socialist’ and ‘democratically socialist’ shows that the public does not fear the term. For me, attempts (by David Cameron and other members of the political class) to assert that socialist ideals make him unelectable is a futile approach that comes across as out of touch with popular sentiment. The increased freedom of socialist thought even extends to American politics, as shown by the popularity of Bernie Sanders, especially significant in a political system that has until quite recently held Communism and terrorism to be the same. Evidently, our cultural understanding of socialism, particularly for the millennial generation, is no longer marred by the failures of the USSR. Historians have recognized that the Soviet economy was just one of multiple socialist models, adding into the discussion the relative success of Nordic democratic socialism in protecting its vulnerable, seen in the low poverty rates of Sweden (9%) and Denmark (5.4%). The election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader and subsequent growth in the party illustrate the appeal of far left ideals to a huge constituency of broadly progressive people who were disengaged with elite politics, yet who involve themselves to profound effect when political activity offers real hope of change.

On a final note, it is important we differentiate democratic socialism, as propagated by Jeremy Corbyn, from the political tradition of Communism, which has to do with revolutionary political change and thus once frightened many of the older generation. The notion that capitalism will fall and a final socialist end state will emerge is not what is being put forward; rather it is an emphasis on achieving socialist goals such as worker empowerment, the even distribution of wealth and income, universal access to health care, education and other essential services, all through representative democracy. Personally, I am just as wary of a ‘pure socialist utopia’ as I am of a capitalist one, but clearly both philosophies can benefit us. It is encouraging that in the United Kingdom and across Europe the irrational fear of the far left is dissipating, and we are remembering that many milestones in humanitarian reform that we hold dear today, such as free health care and a financial safety net for those most vulnerable, have come from the socialist tradition. Corbyn is certainly reminding us of that.

Cover Photo: Gary Knight (Flickr); Licence: Public Domain (CC0 1.0)